Welcome one and all to the ninety-seventh volume of the Areopagus. No introductory frills here — this will be a more express version of my usually wordy missive. Another seven short lessons on art, architecture, music, and history begin…

I - Classical Music

“Dormi o fulmine di guerra”, from La Giuditta

Alessandro Scarlatti (1693)

Performed by Alessandro Stradella Consort & Estevan Velardi

Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio (1602)

This gentle, touching piece of music is an aria (a self-contained song within a larger work) from one of Alessandro Scarlatti’s oratorios, called La Giuditta. Its subject is Judith, of the eponymous book in the Old Testament. Oratorios are similar to operas. The difference is that oratorios are usually performed as a concert (i.e. rather than in a theatre, with full costumes and production, like operas) and are normally religious in nature. This aria’s title, Dormi o fulmine di guerra, translates to “Sleep, Oh Lightning of War.” It is a lullaby for a general called Holofernes. Upon falling asleep he will be beheaded by Judith, a scene painted most notably by Caravaggio (included above). But, before such violence, we hear this enchanting song.

Like so much Baroque music, Scarlatti’s La Giuditta gives an impression of immense sophistication and completeness — the music feels just right. That being said, the sophistication of the Baroque sometimes veers into frivolity; what is formally impressive can end up feeling a little too precise, almost hollow. But not here! Scarlatti infused Dormi o fulmine di guerra with extraordinary emotional delicacy and thereby created one of the most meltingly beautiful songs ever composed. But that (among other things) was Scarlatti’s legacy during the Baroque Era — to make music ever more emotionally expressive.

II - Historical Figure

Jocelin of Brakelond

A colourful name for an essentially regular man of his times. Who was Jocelin of Brakelond? A monk. When did he live? During the 12th century. What can we say about him? He was a member of the Benedictine Order and lived at the Abbey of Bury St Edmund’s, in eastern England. Little remains: a few towers and gatehouses. The rest, as with most English abbeys, survives as stumps of crumbling masonry. How can we imagine what life was like for Jocelin among these ruins?

Well, Jocelin of Brakelond decided to write an account of life at the Abbey of Bury St Edmund’s. It starts when a man called Hugo was Abbot, in 1173, and thereafter describes life at the monastery under its next Abbot, called Samson, through to the year 1202. So this is not a grand historical chronicle like that of Froissart, nor an insight via passionate epistles into two of the Middle Ages’ brightest minds, like the letters of Abelard and Heloise. It is not even, like William Harrison’s Description of England, compiled in the 1570s, a careful and scrupulous investigation into the state of a nation. It is, quite simply, what one ordinary monk called Jocelin thought worth writing down about his life in a monastery during the 12th century. And this is precisely why it matters, what makes it such a fascinating, joyous, and useful read.

Normally I like to quote at length; here I offer a single excerpt from Jocelin’s rather gossipy chronicle. It says enough. This passage concerns a large fish pond built by Abbot Samson — one that annoyed everybody else in the area:

He built up the bank of the fish-pond at Babwell so high, for the service of a new mill, that by the keeping back of the water there is not a man, rich or poor, who has land near the water, from the gate of the town to Eastgate, but has lost his garden and his orchards. The pasture of the cellarer, upon the other side of the bank, is spoilt. The arable land, also, of the neighbouring folk has been much deteriorated. The meadow of the cellarer is ruined, the orchard of the infirmarer has been flooded by the great flow of water, and all the neighbouring folk are complaining thereof. Once, indeed, the cellarer argued with him in full chapter, upon this excessive damage; but he, quickly moved to anger, made answer, that his fish-pond was not to be spoilt on account of our meadows.

Such was Jocelin’s style and will: to record, in simple language, what it was like to live in a 12th century monastery. So consider this a reading recommendation for anybody curious about life in the High Middle Ages. Jocelin’s Chronicle of the Abbey of Bury St Edmund’s is very short, very readable, and available online for free.

III - Art

Pennsylvania Station Excavation

George Bellows (1907)

At the beginning of the 20th century a group of painters reshaped American art. They turned away from the academies (as the Impressionists did in France three decades earlier) both in subject and style. Gone were the idealised subjects of high society and (as they saw it) the cold conventionalism of 19th century art. In their place came dynamic brush-strokes and vivid colours — along with scenes from ordinary life, however filthy or mundane. Their goal was to depict the real America. This group was based in New York. And, although never formally united by a manifesto or institution, they have come to be known as the Ashcan School — it was an insult they happily adopted as a name. They were part of a broader movement in arts and culture, known (for obvious reasons) as American Realism. Among them were wonderful painters like Robert Henri, Everett Shin, and George Luks. Another was George Bellows.

Bellows’ paintings are a catalogue of wonder — he seems to combine that French, Impressionistic mastery of colour and light (epitomised by Monet) with an American eye for rural (think of Grant Wood) or urban (think of Edward Hopper) details.

Pennsylvania Station Excavation, from 1907, depicts preparation for the building of Old Penn Station, a colossal Beaux-Arts train station demolished in the 1960s. Here we see Bellows at his finest, capturing a moment of vigorous American urbanism. His style, of fluid brushstrokes and vivid colours melting together, gives it urgency and atmosphere; we can almost hear the crash of metal and stone. There is hope here — a bold, progressive, industrial hope — but also hardship, and a sense of the material difficulty of life in those days. And, stepping back from the details, Bellows gives us a work of sensorial, technicolour joy. His eye for light — red sun behind rising smoke, shadows of industry looming over snow — was supreme. Such was the Ashcan School; such was George Bellows.

IV - Architecture

The Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel has been in the news again; no better time, then, to talk about it. First: what does “Sistine” actually mean? The chapel was commissioned in 1473 by Pope Sixtus IV and completed nine years later. His name in Italian was Sisto and the chapel was named after him, hence “Sistine” Chapel. Where is it? Within the Apostolic Palace — the Pope’s official residence — in the Vatican City. But, for such a famous building, it isn’t noteworthy, certainly not impressive, from the outside.

After Sixtus’ chapel was completed he had it decorated by the leading artists of the day, including Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino. And yet, perhaps understandably, their fame has been eclipsed by Michelangelo’s ceiling. Most remarkable about this ceiling is that, when Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II (known as the “warrior pope”; his name was inspired by Julius Caesar) he had never made any paintings of such scale. He was already Italy’s leading sculptor, having made the Pieta and David, but decorating a papal chapel was something else entirely.

Well, aged 33, Michelangelo was offered the equivalent of about $500,000 and got to work. The ceiling had originally been painted like the night sky, with stars over a blue background. This was removed for Michelangelo, who painted on freshly laid plaster each day. Popular myth says he did so laying on his back, but the truth is that he painted it standing, bent over backwards on a raised scaffold. This gave him back problems for the rest of his life — and he even wrote a poem about it:

My belly, tugged under my chin, ‘s all out of whack.

Beard points like a finger at heaven. Near the back

of my neck, skull scrapes where a hunchback’s lump would be.

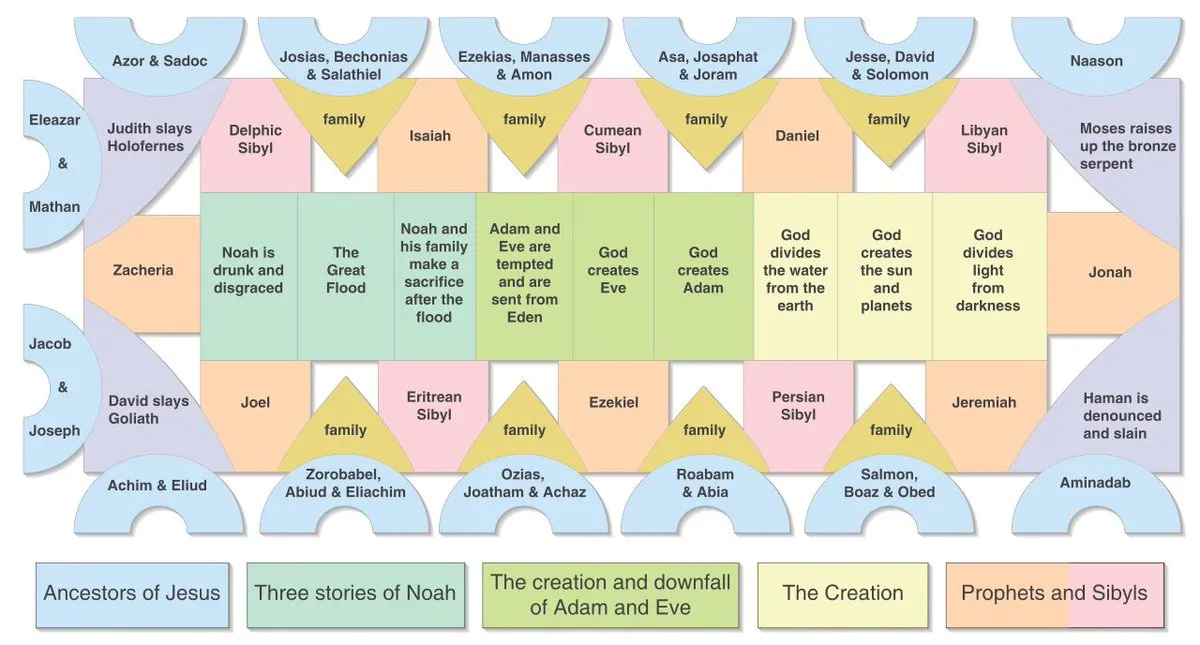

Below is the plan of his design for the ceiling: a complex array of stories from the Old Testament, especially from Genesis, and of prophets and other biblical scenes, along with a motley crew of cherubs and suchlike. How to make it clear? The ceiling’s surface is smooth, but Michelangelo organised his figures among painted architectural details to create order and conjure a sense of depth.

So this was to be totality of scripture made visible in art — there are more than three hundred figures in all. And the most famous parts (think of God and Adam, reaching out to one another) are those he painted last. He started with the minor scenes because he wanted to perfect his technique before attempting to paint God — it’s easy to forget that Michelangelo was literally learning on the job. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is also filled with acorns. Why? Because Julius II was born Giuliano della Rovere, and Rovere means oak in Italian. His personal symbol was the acorn and Michelangelo’s inclusion of them was a symbol of his patronage.

When Michelangelo completed his project and the ceiling was unveiled in 1512, it was hailed as a masterpiece and Michelangelo as a genius. That being said, he was a controversial artist whose works inevitably divided people. Most startling was his decision to include five “sibyls” — oracles from the ancient world of Greece, Rome, and Persia. Mixing pagan and Christian figures was, at the time, shocking. Others were appalled by the nudity. But Michelangelo, true to the Renaissance and its revival of ancient art, was inspired by the nude statues of Greece and Rome — hence the muscular torsos and twisting bodies which defined all his painting and sculpture.

The story doesn’t end there. Twenty year later, in 1535, Michelangelo was invited back to the Sistine Chapel by Pope Paul III; this time he was asked to paint the last judgment on its altar wall. Michelangelo had the wall adjusted — so that its top sticks out further than the bottom — and started painting. Over the next six years he broke radically from traditional depictions of the last judgment. His version was far more complex, he didn’t paint Jesus on a throne, he didn’t arrange the angels or resurrected as described in the Bible, and he (again) included figures from Greek mythology.

Jesus hadn’t been portrayed beardless for centuries (which was controversial in itself), not to mention that his muscular body makes him look more like a Greek god. This was highly unorthodox and widely criticised, but Michelangelo the aging master was a law unto himself. And so, even before it was finished, The Last Judgment became controversial. Its departure from scripture, its complex composition, its profusion of violently contorted bodies... as the 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari writes, this was too much for some, especially in a place like the Sistine Chapel:

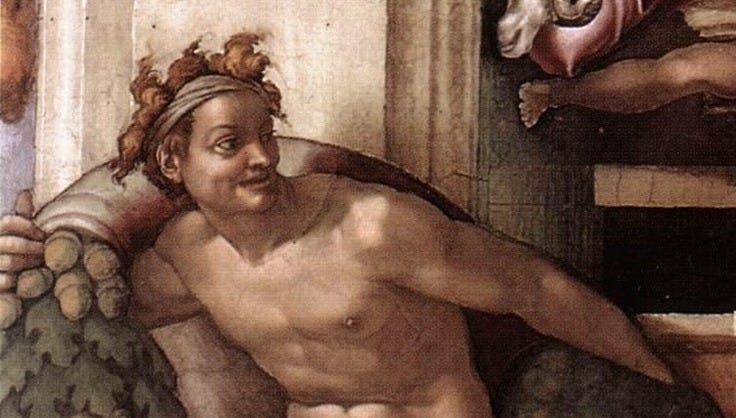

Biagio da Cesena, the master of ceremonies, a person of great propriety, who was in the chapel with the Pope, being asked what he thought of it, said that it was a very disgraceful thing to have made in so honourable a place all those nude figures showing their nakedness so shamelessly, and that it was a work not for the chapel of a Pope, but for a… tavern. Michelangelo was displeased at this, and, wishing to revenge himself, as soon as Biagio had departed he portrayed him from life… in the figure of Minos with a great serpent twisted round the legs, among a heap of Devils in Hell.

Michelangelo’s portrayal of Biagio da Cesena as Minos, judge of the underworld, enwrapped by a serpent, remains:

Here we see Michelangelo’s idiosyncratic, uncompromising personality in full — he used the Sistine Chapel, ostensibly a holy place, to get revenge on his critics. And in the end Michelangelo’s non-scriptural Last Judgement, a wall of several hundred confusingly arranged naked bodies, was just too much: after his death, in 1564, Michelangelo’s former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the nude figures (though many of these have since been removed).

Now, the Sistine Chapel was used continuously for centuries, whether for religious services or for the conclave that gathers to elect the new pope. And so by the 20th century its ceiling had deteriorated, with the paintings covered in soot and grime. In the 1980s there was a major restoration which attempted both to revert damage done by previous restorations and remove the accumulated centuries of filth. From beneath the soot emerged a far brighter ceiling, but some argued that Michelangelo’s subtleties had been lost:

And that is where the papal conclave gathered last week. A somewhat controversial place, at least in terms of its art — and one that, despite its name (from Sisto) and patronage (from Julius) is really defined by Michelangelo, by his radical art and his unusual personality.

V - Rhetoric

Noema

In 1593 the English writer Henry Peacham published his delightfully-titled The Garden of Eloquence. It was a collection of rhetorical devices and terms, spurred on by the Renaissance embrace of Classical learning and all things oratorical, as laid down by the likes of Cicero and Quintilian. Among the fruits of Peacham’s garden was “noema,” a term he explained thusly:

Noema is a forme of speech by which the speaker signifieth something so primly that the hearer must be faine to seeke out the meaning, either by sharpnesse of wit, or long consideration.

The use hereof onely to conceale the sense from the common capacitie of the hearers: and to make it private to the wiser sort, who by a deepe consideration of the saying, are best able to finde out the meaning.

This figure ought to be used verie seldome, and then not without great cause, considering the deepe obscuritie of it, which is opposed to perspicuitie, the principall vertue of an Orator.

Peacham is right to say we should use noema rarely; clarity must be any speaker’s prime goal. But, from time to time, the opposite of clarity — obscurity — is useful. By virtue of being harder to understand, words without clear meaning can be more memorable and impactful. Mystery is powerful. And, though we are safer doing most of our audience’s work for them, it is sometimes worth making them do the work. As listeners or readers we gain immense satisfaction from figuring things out ourselves, and there is a sort of pride in recognising obscure cultural references.

Noema could be (and most often is) when you make a cultural reference that you know only some people will understand. If I compared a politician to Senator Palpatine then only fans of Star Wars would understand; if I said a particular book was as readable as the third chapter of John Ruskin’s Queen of the Air then only those who have read it would know that, in truth, the book I’m talking about is impenetrable.

Otherwise noema can simply be non-referential speech that is obscure or difficult to understand on its own terms, perhaps a line that is poetic in diction. On the front cover of T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, for example, are written the words:

The sword also means clean-ness & death

A highly noemic cover! As a teenager those words stayed with me — precisely because they were obscure, because I could not understand them at first and spent a long time wondering what, if anything, they did mean.

Finally, I suppose, we should say that noema works best when surrounded by perfectly clear and comprehensible language. It is by being placed in a thoroughly clear speech (or piece of writing) that an obscure sentence works best — because the listeners or readers are therefore inclined to think that there must be some meaning to it.

VI - Writing

Wordology

In the last Areopagus I wrote about Sir Thomas Browne, a veritable wordmint who coined new terms (among hundreds of others) like electricity, ambidextrous, and medical. Then there’s William Shakespeare, who added nearly two thousand words to the English language, among them fashionable, alligator, and gossip. Why did they do this? Partly for literary effect (itself a worthy goal) — but primarily because it let them be more specific and refer to something for which there was not already a clear word. So the lesson of Browne and Shakespeare is simple: if you can’t quite find the word you’re looking for… invent it yourself!

But there are two ways to do this. One is by creating something entirely new: a sequence of letters never before arranged in that order and with a wholly unrelated meaning attached to them. I could say that “flozingshrud” refers to the specific feeling you get when a summer day seems to last forever and leaves you feeling drowsy, unable to think or doing anything, in a sort of sad rather than pleasant way. But, writing “flozingshrud”, how would you have known that?

Better, and more useful, is when you combine or modify existing words in a way that makes clear the meaning you’re aiming at. If I said “summerdulled” instead of “flozingshrud” then, used in context, I think you could intuit the word’s meaning — even though it has (as far as I can tell) never been used before. The same is true of “wordmint,” that term I used to describe Sir Thomas Browne. It isn’t in the dictionary. But, I suspect, it made sense to you. We usually speak of “coining” new words and a mint is where coins are made; to call somebody a “wordmint” makes instinctive sense.

Think of Shakespeare. It’s almost wrong to say he “invented” words like bedroom, eyeball, or undress. They had never been used (or written down) before he used them, and they allowed him to write more specifically — but their meaning was obvious to any and all who heard them. So inventing new words is, at heart, about embracing the flexibility and texture of one’s language, about seeing our shared grammar and vocabulary not as representing a fixed and permanent set of rules, but rather as a living, ever-changing inheritance that we are all entitled to engage and play with. As the literary critic and novelist Arthur Quiller-Couch once said, so brilliantly:

Seeing that in human discourse, infinitely varied as it is, so much must ever depend on who speaks, and to whom, in what mood and upon what occasion… it is better to err on the side of liberty than on the side of the censor: since by the manumitting of new words we infuse new blood into a tongue of which (or we have learnt nothing from Shakespeare’s audacity) our first pride should be that it is flexible, alive, capable of responding to new demands of man’s untiring quest after knowledge and experience

I agree.

VII - The Seventh Plinth

May, Maia, Maior, Maiores

All the millennia of our shared human history are contained in the minutest details. May has begun. May. That’s what we call the fifth month. Already that throws up a multitude of questions: what is a month? what is a year? why are there twelve months? And what about… May? A word we have said so many times that it ceases to be noticeable. But why is this fifth month called May, and what does it even mean?

The names of our months come from the Romans — along with our calendar system, which was created by Julius Caesar in 45 BC and refined under Pope Gregory XIII in the 16th century. Caesar’s calendar was based on the much older calendar of the Roman Republic, itself refined several times. Hence September, meaning “Seventh” in Latin, is our ninth month — but this incongruity was also present in Caesar’s time!

Now, the Roman months were named after their original position in the calendar (i.e. November being “Ninth Month”), after historical individuals (e.g. August was named after Augustus in 8 BC), or after gods (e.g. March, once “Martius”, being the Month of Mars, god of war). May falls into this third category. Romans called it Mensis Maia, or Month of Maia. This Maia was originally a Greek goddess who became a Roman one, and whose symbolism was tangled up, for reasons of etymology, with the Latin word maior, meaning “greater”. Thus, alongside her other, pre-existing mythological links to Hermes (messenger of the gods) and Vulcan (blacksmith of the gods), Maia also signified growth. In this way she was further linked to deities of the earth, like Opis, a primordial goddess of crops and fertility. All that makes sense for a month that occurs in spring. But there’s more! Again, for reasons of etymology, the Greek Maia also became associated, for the Romans, with their ancestors — maiores, in Latin, meaning just that. So is May also… the month of ancestors?

All that sounds confusing — because it is. These questions about why May was called May in the first place were as interesting and difficult to answer for the ancient Romans as they are for us. I think it is wonderfully curious that even in 2025, with all our modern technologies and ideas, our satellites and smart phones, we are stuck with a calendar system which has names neither we nor the people who invented it over two thousand years ago fully understand. Such is history.

Question of the Week

Last time I asked you:

Is there such a thing as fate?

And here are some of your answers:

Jill M

As drawn as I am to art, history, and literature, I am also interested in science and it is science that provides my answer that, yes, there is such a thing as fate. In a classical causal argument, from the moment matter came into existence, each reaction led to the next and the next and the next. The vastness of time puts it nearly beyond human comprehension that somehow, every particle interaction over billions (and billions) of years led us here, to the question about fate being asked and this answer being written. I find a counter to this, one involving probabilities and randomness that allows for free will—the idea that some things just happen with no prior cause—much less compelling.

Science aside, I am as susceptible to the romance of fate as anyone else. So, on a much smaller timescale, I don’t ask what caused your Twitter account to appear in my feed, I merely accept it. Then Areopagus came to my attention. So here we are at the same point, with fate leading you to ask the question and leading me to read and to answer. Much less cold and calculating.

Everything is meant to be.

David R

By coincidence, the book I am reading this week-end discusses medical diagnosis and the issues arising from “over-diagnosis”. Today, scientists can analyse your genome and make predictions about what health issues you are going to have to deal with, for the rest of your life. Having just read the chapter on Huntington’s Disease, I find it difficult to deny that there is such a thing as “fate”.

If one of your two parents has the Huntington’s gene then, through biological reproduction achieved by these two genomes, there is an exactly 50% chance, no more and no less, that you too will have the Huntington’s gene, and no doubt what grim implications that presence will have, ever-increasingly, for the rest of your life. For the parents, thinking of having another child, that has been their “fate” (whether they knew it or not) since the dawn of time, scientific fact, ordained by the almighty whatever, dictated by DNA, and no mere human can do anything about it.

Not yet anyway. But science continues to advance. It seems reasonable to suppose that, before long, it will be possible to excise the genetic variant before any act of conception is performed, thereby elegantly finessing out of what was, until then, pure and certain fate.

So: My answer. The question might be a classic but is forever topical. Fate exists, at least today, but as we humans continue to understand more fully what it means to be human (as opposed to an artificial intelligence) none of us knows whether it will still exist tomorrow.

Yedi Z

Your life’s path is not set in stone. Free Will means factors such as choice, opportunity, coincidence and timing have an impact. The terms “fate” or “destiny” imply that you’re not in control. Yet your success will come largely through your own efforts plus intention. The results can be called “luck”, but it’s the many small steps you have taken which place you in “the right place at the right time”.

Now, for this week’s question — a challenge, based on today’s Writing section:

Invent a new word.

Email me your new word, with its meaning, and I’ll share it in the next Areopagus.

And that’s all

Clouds rushing overhead. Sometimes so sluggish, almost permanent — sometimes racing toward a far-off destination with an urgency beyond human understanding. Or, as the great Hindu poet Kalidasa wrote nearly two thousand years ago, might they be our friends, taking messages to distant loved ones for us?

Learn first, O cloud, the road that thou must go,

Then hear my message ere thou speed away;

Before thee mountains rise and rivers flow:

When thou art weary, on the mountains stay,

And when exhausted, drink the rivers’ driven spray.

Until the next Areopagus — I wish you all a merry May. Adieu!

Yours,

The Cultural Tutor