Welcome one and all to the eighty seventh volume of the Areopagus — and we embark once more on a journey through time and space...

I - Classical Music

Summer Night on the River

Frederick Delius (1911)

Performed by the Hallé Orchestra

Moonlit Night on the Crimea, Gurzuf by Ivan Aivazovsky (1889)

Summer Night on the River, together with the more famous On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring, formed Frederick Delius' Two Pieces for Small Orchestra. They are both symphonic poems: one-movement compositions intended to evoke a particular place or feeling. What I love about Summer Night on the River is how it conjures an atmosphere rather different to the one usually created by summer-inspired music. This is not purely peaceful, not wholly languid or heat-dazed. There is an edge of mystery to Delius' little meditation, even a hint of darkness. Such impressions are surely the result of Delius' use of chromaticism; notice the slight strangeness here, the sporadic atonality, the sense of unresolved notes. With it he leads us along a seven minute musical journey that is elusive, almost unsettled, and gorgeously expressive — and gives us a different sort of summer.

II - Historical Figure

William Harrison

Voice of the Past

William Harrison was a priest and scholar who lived in 16th century England. To give his biography as nothing more than that sentence would not be an error, and it would not understate his role in history. No, William Harrison is not a man who will be found in lists of "the most influential people you've never heard of" or any such thing. He was, by all accounts, a relatively ordinary man of his time — and that is what makes him special.

See, in the 1560s he became involved in a fascinating project. It had started in 1548 with a printer called Reginald Wolfe, who would later become Master of the Worshipful Company of Stationers under Queen Elizabeth. He had set himself the lofty goal of creating:

a universall Cosmographie of the whole world, and therewith also certaine particular histories of every knowne nation.

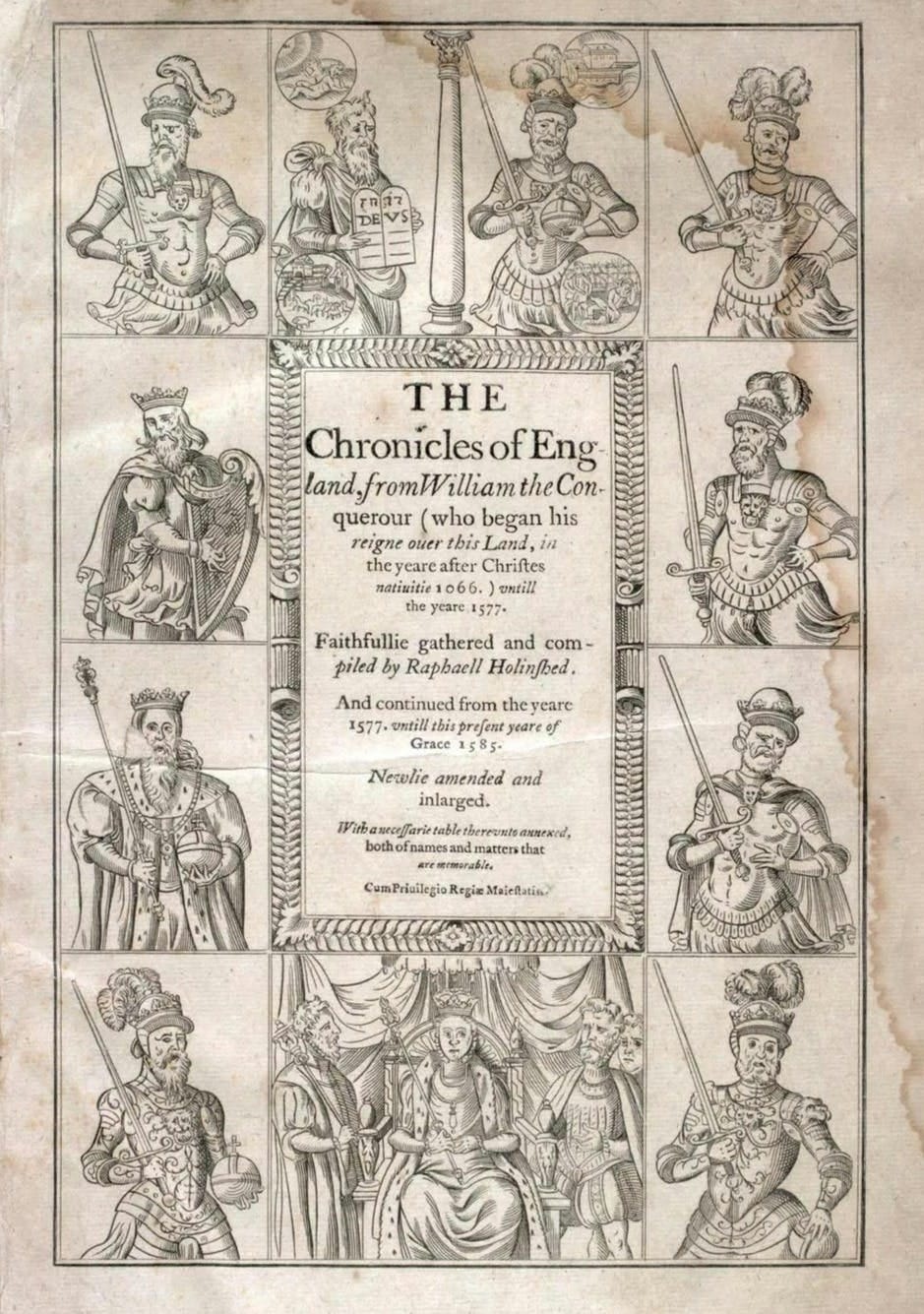

Wolfe could not complete this monumental task alone, so he ended up hiring Raphael Holinshed and William Harrison, among others, to help him. When Wolfe died his fellow publishers scaled down the scope of this project to the British Isles alone — that is, rather than the whole world. By 1577 the first edition was finished: a sort of encyclopaedia both of British history and of life in modern Britain. Holinshed had taken charge of the historical part and so the work has come to be known as Holinshed's Chronicles. This was a major source for Shakespeare's history plays, and for other Elizabethan writers like Edmund Spenser and Kit Marlowe.

What about William Harrison? He was tasked with compiling the review of modern life. And yet, as he says in the preface:

I must needs confess that until now of late... I never travelled forty miles forthright and at one journey in all my life.

Despite having not much travelled Harrison was a passionate historian who collected old maps, letters, coins, and all manner of curiosities. He consulted these for much of his work, rifling through libraries and especially through the notes of an earlier Tudor historian called John Leland. And, in the end, he did travel — up and down the country, speaking to anybody who would lend him a penny's worth of thoughts. Thus Harrison created his Description of England. It is a vivid and all-encompassing portrait of the Elizabethan Era, one for which Harrison found no detail or tangent unworthy.

What can we learn from Harrison? It sounds silly, but pretty much everything. The various chapters of his Description range from the total number of parishes in England to its various species of birds and beasts, from criminal justice to local nicknames for alcohol. What time of day did people used to eat? Harrison tells us:

With us the nobility, gentry, and students do ordinarily go to dinner at eleven before noon, and to supper at five, or between five and six at afternoon. The merchants dine and sup seldom before twelve at noon, and six at night, especially in London. The husbandmen dine also at high noon as they call it, and sup at seven or eight; but out of the term in our universities the scholars dine at ten.

Much of the Description was drawn from first-hand investigation, some of it rigorous and but some of it purely anecdotal — like this excerpt from a passage where Harrison is discussing the snakes of England:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Areopagus to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.