Welcome one and all to the sixtieth volume of the Areopagus. We begin with an exciting announcement: not so long ago I spoke with David Perell, the founder of Write of Passage and my patron, about both my personal story and the trials and tribulations of writing in general. Our rather vigorous conversation has now been released as one of the inaugural episodes of his new podcast, How I Write. You can listen to the full thing on YouTube or on Spotify. Should you choose to do so then I hope it transpires to be a not unfruitful use of your time.

Back to the Areopagus. This week's, like the last, is a special volume — a double-header, if you will. For I was lucky enough to have spent some time in Verona recently, that fine and ancient city in northern Italy.

It would be unconscionable for me not to write about Verona, then. However, I must be disciplined. Unfettered by editorial rigour I would end up writing for you a meticulous and sesquipedalian guide to the city's entire history and its every street and stone. This I ought not do. Instead I have chosen several specific subjects to write about — largely relating to Verona's architecture, urban design, and art — which I think you shall find interesting and in the reading of, I hope, gain some useful knowledge thereby. This new format I shall call The Anatomy of a City.

Musical Prelude

We begin with the music. And though it was tempting to include some opera — for, as you shall see, few cities have such a close relationship with opera as Verona — I think it might be more appropriate to opt for a composer born not so far from the city in the year 1750: Antonio Salieri. He is more famously associated with Vienna, for that is where Salieri made a name for himself as one of the crowning jewels of the Classical Era. But popular legend casts him as little more than the bitter and jealous rival of Mozart, in part because of the play and film Amadeus. So let us remove Salieri from Mozart's shadow and take him on his own terms, for he was a supremely talented and vastly influential composer in his own right: Franz Schubert, Franz Liszt, and Ludwig van Beethoven were just three of his many students.

Here we have Salieri's Requiem in C Minor, which was written in 1804 but not performed until his own funeral in 1825. A requiem is normally a piece of music composed specifically for a Catholic funerary mass — the Requiem Mass — in which its texts are set to music. But this subgenre of liturgical music, perhaps because of its emotional and spiritual potency, became a separate musical form all of its own, often written for performance in the concert hall rather than the church. Composers like Mozart, Verdi, Brahms, and Dvořák have all written their own requiems. Here, then, was Salieri's contribution to this time-honoured musical tradition. The painting is Supper at Emmaus, made in 1560 by Verona's most famous artist, Paolo Veronese.

Anatomy of a City

E alora che è finì tuto el sussurro / speciarla zò ne l'Adese, dai ponti,

e comodarla mi, muro par muro, / tuta forte nel çercolo dei monti...

So, where to begin? William Shakespeare described Verona as "fair" in the second line of Romeo and Juliet. Much of the city's international renown rests on its association with the world's most famous romantic tale, but we would be much amiss to think of it as no more than the setting for Shakespeare's great tragedy. Its streets may well have seen blood-feud and star-crossed romance between Montague and Capulet, but they are only a precusor to the delights and intrigues of Verona proper, home to some of the purest and finest Medieval architecture and urban fabric in all of Italy.

And yet it is the strictly Medieval quality of this city which perhaps makes it seem so believable that Romeo and Juliet, wholly fictitious or mythically expanded from some kernel of truth, really did walk these marble streets and fall in love at some banquet or ball in one of the grand palazzi of the noble families, with their cloistered courtyards and sombre towers, and that Romeo later stole away through the night beneath the peeling plaster and ogival windows of Verona's narrow alleys, where even today after dusk one still sees solitary figures, perhaps lovers, slipping out of sight amid the shadows thickly gathered under the arcades and loggias. Let us journey, then, to this fair and noble town...

The Adige

The Adige is the second-longest river in Italy after the Po. It rises high up in the Alps, near the Reschen Pass on the Swiss-Austrian Border, and then flows almost directly south for about one hundred miles, past Lake Garda, where it turns suddenly east, crosses the Veneto Region for another hundred miles, and drains into the Adriatic.

Midway along its course, not far from Garda, is the city of Verona — or, as the Ancient Romans called it, Colonia Verona Augusta Nova Gallieniana — built on a loop in the milky-white Adige. It lies about halfway between Milan to the west and Venice to the east. In the north one sees the foothills of the Alps, usually clad in a heavy blue haze, and southwards stretch out the fields of the great Lombardy Plain, a vast and fertile basin between the Alps and the Apennines, all the way to the horizon.

Scarlet and Cream

So, we are in Verona. The architectural motif that defines this city is stripes of tuff (a type of volcanic rock) and brick. The number of buildings decorated this way — or, rather, built this way — is beyond counting. It seems to have been the standard choice of Verona's Medieval architects, from the 11th century onwards, to build according to this simple but delightful model. Two or three courses of thin bricks, once blood-red and now a sort of pale scarlet, followed by a course of blocks of cream-coloured tuff, repeated from floor to ceiling. Arches too, whether pointed or round, we find in similar bands of red and white.

This pattern is everywhere. We find it among the most important secular buildings in the city, such as the 12th century Palazzo della Ragione and the colossal Torre dei Lamberti soaring above:

And at most of the city's several dozen churches, like San Giovanni in Foro. Here, beneath the cornice, you can also see cobbles set in alternating diagonal bands, which appears to have been a similar architectural motif dating back to even older, Carolingian times. This method endures in a few places around the city, especially among its oldest and least-altered churches, and thus usually the smaller ones:

The brick-and-tuff motif also defines Verona's most ordinary buildings. Here, photographed up-close so you can really get a sense of the materials used, is an unremarkable five-storey block of Medieval apartments in the old town, where we can also see the toing and froing of the ages, as doorways are filled in, walls repaired, and windows knocked through. One never tires of this pattern — of the simple delight of the materials, of their textures and warm colours, and the basic of joy of red and white stripes. And, I think, its ubiquity lends the city a cohesive atmosphere and a strong architectural identity.

At the Doors of San Zeno

Zeno is the name of Verona's patron saint — a man who, because of various legends associated with his life, also happens to be the patron saint of fishermen. He was born in North Africa and became bishop of the city during the 4th century. Verona's most famous church is named after him: the Basilica di San Zeno Maggiore, where its namesake is also buried. There was a much older church and abbey here, dating back to the time of Saint Zeno himself, but that was destroyed during an earthquake in the year 1117. This was a cataclysm which ruined much of Verona's older Medieval infrastructure and inculcated a vast rebuilding project during the zenith of the age of Romanesque architecture. What we see now is the basilica built then, during the 12th century, with those same scarlet and cream stripes of brick and tuff running along its walls. Here is a view of the southern side of the basilica, with its belfry behind, looking up from the cloister:

Romanesque was a style of architecture which emerged during the High Middle Ages before the rise of the Gothic. It is defined by the use of rounded arches (which the Romans had used, hence Romanesque, and in contrast with the pointed Gothic arch) along with very small windows, minimal buttressing, huge cylindrical pillars, and an overall atmosphere of robust, structural, monumentality — none of the soaring arcades, pinnacles, flying buttresses, large windows, and sophisticated tracery of the Gothic here.

There are many things one might remark of the wonders of the Basilica of San Zeno. But, given that I am writing a newsletter and not a book, I shall limit myself. And at San Zeno we simply must begin with the bronze doors, for there is hardly anything else like them, of their age, in Europe. Now kept inside, they were once the centrepiece of an immense sculptural ensemble at the church's west entrance. Here we see a smooth and highly typical Romanesque façade of relatively undecorated marble — aside from its slender pilasters and serrated corbelling the subtle hues of its timeworn stone, which glow a gentle rose-gold, are deocration enough. Above there is the rose window sculpted by Master Brioloto in the late 12th century, designed to represent the Wheel of Fortune, and below it an elaborately decorated portal supported by columns resting on two lions, flanked by bas-relief panels depicting scenes from the Old Testament and the life of the ancient King Theoderic; these were made by Master Niccolò and his apprentices earlier in the same century.

And here are the bronze doors, divided into forty eight panels and interspersed with various grotesque faces and decorative bars. We are told that three different master artisans contributed to the doors, beginning in the 11th century and concluding in the 12th. On the left hand side are stories from the New Testament and on the right stories from the Old Testament, along with scenes from the life of Saint Zeno. These photographs do not quite convey the sheer size of these doors, nor — by way of their blackened metal, warped and worn and chipped — the peculiar impression of immense age one senses when standing before them.

Well, what do you see? These are not sophisticated sculptures. And we would be forgiven for thinking — right, even, to think — that there remains a certain barbarity to this sort of art, especially in the grave, snarling, atavistic faces at the corners of the panels. The Renaissance was still hundreds of years away, and at these bronze doors we can feel the not-so-distant shadow of the Dark Ages, and sense an art form still struggling to emerge from the violence and chaos of the preceding centuries, still searching and a long way from discovering technical supremacy, detailed realism, and sophisticated beauty. But realism and beauty were not what these metalworkers had in mind: their objective was an absolute clarity of storytelling. And this they achieved flawlessly. For those familiar with the stories of the Bible it will be immediately apparent what most of these panels depict — and, even for those only vaguely aware of biblical history, a great many of them will also be clear. Take Noah's Ark:

Or some scenes from the New Testament:

There are no extraneous elements. We have only the purest and most vital details at hand so that we are left in no doubt about the story being told — a Bible for those who could not read, and a vivid visual account of scripture even for those who could. And in this way I think there is almost something more pious about this sort of religious art, which seeks neither to be beautiful nor sophisticated nor impressive, but which hopes only to be truthful and understandable, than all the greatest achievements of the High Renaissance.

The human figures may be somewhat rudimentary, and they aren't particularly lifelike or naturalistic, nor even emotionally expressive, and their faces, forms, poses, and clothes are all rather crude. But none of this detracts from the potent storytelling power of the bronze panels or the clarity of their epic narrative cycle, nor from the faithful piety of their intention to convey and describe the stories believed by the sculptors and worshippers at San Zeno to be truthful. It is this very simplicity of form and austerity of design, this immediacy of purpose and spiritual honesty, that makes the doors so striking, so memorable, so powerful!

Two things more I wish to mention about the Basilica of San Zeno. Here, inside, is a fresco about seven hundred years old. What surprised me most was that the marks on its surface, which seem at first glance like the usual wear of the passing epochs, are actually all graffiti. People have been engraving their names into this fresco (of Mary!) for hundreds of years; some of the dates scrawled onto the plaster are from the 17th and 16th centuries, or even further back. A reassuring reminder, I suppose, that irreverence for the past and a disregard for objects of historical and cultural value — and that peculiar human urge to record our names in wood and stone, saying "I was here" and adding a date — is nothing new.

I should also mention that the crypt of the Basilica di San Zeno, resting place of the patron saint and a dim and atmospheric chamber where the broad, load-bearing columns that support the chancel gather like a stone forest, and where daylight barely penetrates these oppressive shadows, though glinting here and there on San Zeno's sarcophagus and picking out details in the marble foliage of the carved capitals and fragmented frescos above, is where Romeo and Juliet were said to have been married in secret. This is one of many places in Verona where the Middle Ages come suddenly, secretly, to life.

Santa Anastasia

San Zeno is to the west of the old town, out beyond the monumental walls of the Castel Vecchio. But now we are in the heart of Verona, lost among the streets splayed out in the loop of the Adige where its monuments, squares, and churches are most concentrated. You can see the campanile and buttresses of the Basilica di Santa Anastasia in the upper left of this photograph:

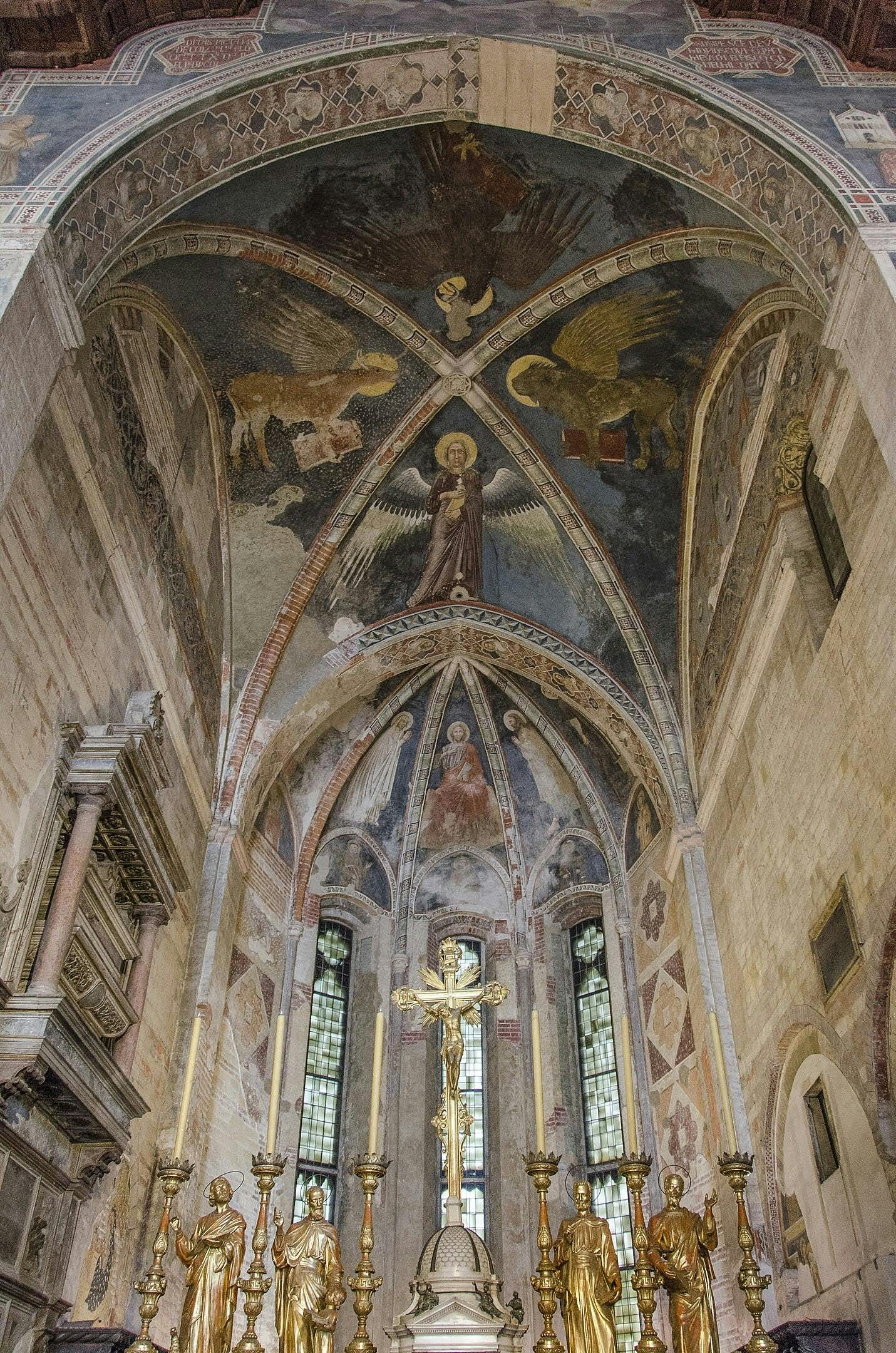

The construction of the Basilica of Santa Anastasia began in the late 13th century on the site of a much older church of the same name. Work continued intermittently for the next two hundred years, as the Gothic arrived and overtook the Romanesque, with further amendments during and after the Renaissance, until it became Verona's largest church. As such, one can see inside the slow but steady transformation of art from Romanesque (influenced in Medieval Italy by the Byzantines) to Gothic to Renaissance and all the way to Baroque. The walls and chapels of Santa Anastasia are a very literal timeline of the evolution of painting.

We begin with something like the Last Judgment, a fresco painted in the chancel in the mid-14th century by a local artist called Turone. It is still — with its lack of depth or natural perspective, the statuesque anatomy of its clustered figures, and the preference for narrative clarity over "realism" or "beauty" — very much under the influence of quasi-Byzantine, High Medieval art:

Then to a damaged but vibrant painting of St George and the Princess by Pisanello, from the early 15th century. This is the epitome of a style known as "International Gothic", which flourished just before the Renaissance. It incorporated new techniques of depth and perspective, along with a greater attention to light, shading, and modelling, but without letting go of that Gothic love for detail, pattern, and a tendency to squash things together — buildings, landscapes, crowds — to fit in as much as possible:

And then all the way through to the Renaissance works of Liberale da Verona, painted at some point around the year 1500, when the harmonious, idealised realism of Florentine art had already started to conquer the rest of Italy, and soon the rest of the world with it.

The only other thing I should mention about the interior of Santa Anastasia is its floor: a vast sea of interlocking tiles created by Pietro da Porlezza in the 1460s. It is a delight of texture and colour, of clouds of black, white, and orange marble, each minutely varied with their veins and flecks and imperfections, polished to a perfect glaze by the passing feet of centuries of worshippers. So often in churches we are drawn to look up — here, for once, my eyes were fixed on the ground.

For some reason the façade of Santa Anastasia was left, and remains, unfinished. There is a marvellous Gothic portal to welcome us in — notice the pointed arch and its rolls of banded archivolts, in opposition to the suspended, round portal of San Zeno — but the rest of the church's western front is nothing more than a wall of uneven bricks, noticeably rough around the windows. Those horizontal ledges projecting from the face would have been used to fix and support the slabs of marble cladding which were never added. It makes for a strange impression, then, and rather understates the glory of its interior.

But this reveals an important difference between Gothic architecture in Northern Europe and in Italy. Whereas with the cathedrals of France, say, what we see from the outside — the large blocks of limestone, alive with buttresses and blind arcades and statuary — represent the actual structure of the entire building, it was standard practice in Medieval Italy to build a church with bricks and then face them with marble. Think of the famous Duomo in Florence, with its bands of alternating white and black stone. A photographic comparison between the Florentine Duomo of the early 19th century, before its façade was finally added, and today, shows what lies beneath.

I don't think Santa Anastasia looks any the worse for its unfinished exterior, because well-laid bricks are never ignoble. And, if anything, it lends the church a character curiously alive, as though it is still being built, which is a wonderful way to feel about such an old building.

Given that we are already discussing the difference between northern and southern European architecture in the Middle Ages, I must comment on that which first struck me about all Italian churches — their small windows. In the Gothic cathedrals of France, Germany, the Low Countries, and Britain we are accustomed to walls of coloured glass interlaced with curvilinear stone tracery. So much of Northern Gothic architecture seems almost subservient to the window, as though apertures filled with stained glass were the crowning achievement of ecclesiastical architecture, and that all those flying buttresses and fine vaults were working in structural harmony only to create windows as tall and broad and grand as physically possible.

Not in Italy. Here the churches have small windows and the art is provided by frescos covering every inch of available surface rather than by stained glass. Of course, northern Gothic churches were also once heavily frescoed, much like Romanesque churches before them, and it is only time and iconoclasm that has seen them fade, but there is a significant difference in design culture here, between Northern and Italian Gothic. Alas, now is not the time to explore this divergence — or its implications, which may have something to do with the peculiar importance of painting in Italy and its role in the Renaissance — and so, noted, we must walk on.

The Monsters of the Duomo

Verona Cathedral, or the Duomo, formally called the Santa Maria Matricolare, is a curious building. How much one might say about the Duomo! Note, again, the red-and-white motif that defines Verona, and another austere Romanesque facade offset by the pink-gold glow of its marble facing.

But this apparently pure Romanesque exterior — similar to that of San Zeno, and also built after the earthquake of 1117 — belies a wholly different interior, perhaps hinted at by the pinnacles along its roofline. Inside, the Duomo is a church remodelled with Gothic vaults and cluster-columns in bright red Veronese marble during the 15th century, and then refitted entirely in the following centuries with a wave of Renaissance and Baroque impositions.

Let us remain outside, then. For if you approach from Santa Anastasia, along the Via Duomo, you shall see in the distance — framed perfectly by the long expanse of the dark and narrow street, gleaming in the light — a doorway, the south prothyrum of the Duomo. It is nearly nine hundred years old and dates to the Romanesque phase of construction during the early 12th century. Pelegrinus is the name of the sculptor who made it.

If ever you wanted to understand High Medieval sculpture, still Romanesque but verging on Gothic, then Pelegrinus' portal will tell you everything you need to know. Notice the lack of what we would call "realism", for his human figures and animals are rather crude, almost childish, in form and face. But, if we set aside our pretensions for a moment and embrace the pure, untrammelled, expressive and symbolic force of this doorway — with its myriad details, the foliage and the pattern, the faces and bodies entangled therein and looking down on us, all of it freed from artistic constraint, and the fabulous and fantastical beasts, the ghastly dragons, and the little songbirds among them, guardians or tormentors, and the apotropaic savagery of it all, and the inexplicably asymmetrical columns, one of porphyry dark as night and the other of pale marble, different because Pelegrinus had simply to work with whatever materials he could get — then we shall understand a little better, I think, how Medieval people felt and thought about the world.

And my favourite detail of all: this proud and noble lion... with a dog(?) biting his backside.

The baptistry of the cathedral, known as San Giovanni in Fonte, has retained its Romanesque appearance. And the star of the show here, perhaps of all the cathedral complex — even more so than Titian's altarpiece — is a monumental baptismal font carved in the 12th century by Brioloto, the master mason responsible for the rose window at San Zeno. I mention this simply to give you some sense of what it must have been like in those long decades of construction after the earthquake, when all this "history" was very much alive and the city must have been a veritable construction site, with artisans like Brioloto going from one project to another and directing a whole team of assistants and labourers in the course of his painstaking work.

Attached to the Duomo is the Church of Santa Elena, where Dante Alighieri himself gave a lecture on the 20th January 1320 entitled Quaestio de Aqua et Terra — the Question of Water and Earth. Part of Santa Elena, though it is primarily a Romanesque-Renaissance hybrid, comprises the ruins of a truly ancient church, Verona's very first, from the 4th century AD. We must also observe the western entrance of the Duomo — for this, like main portal of San Zeno, was made by Master Niccolò. It is another masterpiece of Romanesque sculpture, complete with an elaborate array of stories and statues which we have not the time to review in any detail here.

Arche Scaligere

As the Medicis dominate any history of Florence, and the Borgias and Borgheses that of Rome, and the House of d'Este that of Ferrara, and the Dandolos of Venice and the Sforzi of Milan, it is the House of della Scalla which — even at a distance of seven hundred years since its fall from power — continues to rule in Verona. The first was Mastino in 1262; in 1387 his descendant Antonio died, bringing an end to the rule of the Scaligers (or Scaligeri, as members of their dynasty were known). These were one hundred and twenty five years during which Verona reached its brief and glorious zenith, ruling over much of northern Italy, and the era when many of its greatest monuments, all constructed in those bands of brick and tuff, perhaps to imitate the red and white stripes of the heraldry of the Scaligeri, were built.

But we shall mention only one here: their ark-tombs, known as the Arche Scaligere, a set of three huge, suspended funerary monuments with pointed, richly ornamented canopies. The original tombs of the Scaligeri had been rather humble, but Mastino II in the early 14th century decided to build for his predecessor Cangrande I — the greatest of all the Scaliger lords — a much more fitting monument. Mastino had a yet grander tomb built for himself, and his son Cansignorio then undertook to commission the most glorious of all. Gone was the Romanesque by this point; here was Italian Gothic at its purest, most vicious, and most refined. Pay attention in the image below to the progression of the three ark tombs from right to left, from Cangrande through Mastino and Cansignorio. In perfect chronological order they portray the sure development of the Gothic, from its earliest days through to its fullest maturity, from simplicity through to complexity.

One wonders if there are any finer or more evocative Gothic funerary monuments in Europe. Most striking about them, enclosed as they are behind a marble wall and a fine iron grille bearing the symbol of the House of della Scalla — a ladder — is how they directly overlook the streets where thousands of people, tourists and Veronese, pass every day, strolling beneath the shadows of the tombs of the lords responsible for so much of Verona's glory and beauty.

Adjoining the enclosure is the church of Santa Maria Antica. This old church became the private chapel of the House of della Scalla, whose members lived next-door, and despite a Baroque overhaul was actually restored to its original, 13th century appearance in the 1890s. A sturdy, gloomy, and atmospheric place, dimly lit and gravely beautiful. This is the best church in which to feel Romanesque architecture in all of Verona.

Walking past the Arche Scaligere we enter, suddenly, into the vast geometry of the Piazza dei Signori, where the high summer sun of Verona glitters on the slabs that pave the square and almost blinds us. But at its centre rises a statue. Our eyes are drawn to it. Larger than life and carved from the purest of snow-white Carrara marble, we find a man deep in thought. He wears a large, flowing robe and a cloth cap. In one hand a book and the other hand brought to his chin in contemplation. A stern face, half-brooding and half-inspired, and a face we have seen before: it is Dante Alighieri.

The aforementioned Cangrande della Scalla brought Dante to Verona when he was exiled from Florence, and this is where the great poet wrote much of Paradiso, the third and final part of his legendary Divine Comedy. There is, indeed, reference to Dante's time here in the poem:

Lo primo tuo refugio e ’l primo ostello

sarà la cortesia del gran Lombardo

che ’n su la scala porta il santo uccello;ch’in te avrà sì benigno riguardo,

che del fare e del chieder, tra voi due,

fia primo quel che tra li altri è più tardo.Your first refuge and your first inn shall be

the courtesy of the great Lombard, he

who on the ladder bears the sacred bird;and so benign will be his care for you

that, with you two, in giving and in asking,

that shall be first which is, with others, last.

The "great Lombard" is Cangrande, by the way. How strange, how moving, to have walked the very streets that Dante walked! Alas, here, in the Piazza dei Signori, more often called the Piazza Dante, for obvious reasons, and colloquially known as the "drawing room of Verona" because it was where the politicians and poets usually luncheoned and drank their coffee, we find the finest piece of Renaissance architecture in the city. It is the Loggia del Consiglio, built in the 15th century and once attributed to the architect Fra Giacondo, a spectacle of classical harmony worthy of any Brunelleschi or Bramante.

Colonia Verona Augusta Nova Gallieniana

Verona, though I have emphasised its Medieval architecture thus far, was once a Roman town — and its streets are plentiful evidence of that fact. For Verona still retains several of the Roman gates which once gave access to the city — and which, in the case of the Porta Borsari, locked between two much newer buildings, has not yet fallen from use as an entranceway to Verona for nearly two thousand years!

Verona is also awash with spoliation. This is, you may recall, the "technique" whereby the remains of an older building, usually a ruin, are taken and reused in the construction of a new one. For example, at the corner of the Via Valerio Catullo (named after the Catullus, Rome's most salacious poet, another son of Verona) we find this striking fragment of Ancient Roman sculpture sequestered and embedded into the wall of an otherwise ordinary building:

The Piazza Erbe is just down the way from the Porta Borsari and the Via Valerio Catullo, adjoined to the Piazza Dante by a narrow but high passage running past the Torre dei Lamberti. This was once the Roman Forum. And so, just as it was two thousand years ago, the Piazza Erbe is still the liveliest part of the city, flooded daily by thousands of tourists and fluttering eternally with the umbrellas and canopies of its traders.

A brief word about the Piazza Erbe. You see, John Ruskin — the great historian and cultural critic of the 19th century — came to Verona several times, usually on the way to or from Venice, and when passing through he stopped to study its architecture and make some drawings of the city. By and large he fell in love with Verona, and it rather delighted me to find that his sketches of the Piazza Erbe could easily have been made in 2023. This drawing, I should remind you, is nearly two hundred years old.

Then there's the Ponte Pietra, a Roman bridge which people say dates back to pre-Augustan times. That would make it comfortably more than 2,000 years old. And this is, in some sense, true. But the Ponte Pietra was almost wholly destroyed during the Second World War — of its five spans only one was not ruined by retreating German soldiers in 1945. Just over a decade later it was rebuilt. Does that mean it isn't Roman? I don't think so. Landmarks all over the world — from St Mark's Campanile in nearby Venice to the Temple of the Golden in Pavilion in Japan — have been rebuilt many times, and we can only thank those who decided seven decades ago to rebuild the Ponte Pietra rather than worry about the "authenticity" of what they were doing.

There are many other Roman ruins — whether entire buildings, sole spoliated columns, or stumps of walls here and there — in Verona, not least the ancient theatre on the banks of the Adige, but we must conclude with the Verona Arena, which is the third-largest surviving Roman coliseum in Italy. Only one fragment of its former three-storey façade remains; what we see is essentially the internal structure of the 40,000-seater stadium.

But the best thing about the arena isn't that it has survived as some museum piece for guided tours. Rather, most extraordinary is that it remains, two thousand years later, first and foremost a fully functioning entertainment venue. See, each summer this arena is home to an internationally renowned opera festival for which the crowds come flocking. Its terraces, just as they were all those epochs ago, are filled with the cheering and applauding spectators, and in the underbelly the arena, in its tunnels and chambers, are found the changing rooms and toilets, the store cupboards and machinery of a working environment. How proud these ancient stones must be that they have not been retired behind plaques and rope-barriers but live on, strong as they were when first laid, reverberating with the sounds of a full orchestra, the adulation of a full crowd, and the arias of Verdi, Puccini, Bizet, Berlioz, and all the rest. What better use could there possibly be for historic architecture — what better way to honour it — than to use it?

Urbanistica di Verona

We end with some general remarks about the city of Verona and its architecture and urban design. For here, I think, there is much in which we can delight — and much to learn! It is very easy to visit a city like Verona and remark on what a pleasant place it is, on how happy and uplifted one feels there, without ever wondering why or, at the most, ascribing it to some generic "Italian sensibility". Not so. There are some very specific things which make Verona, and other cities like it, so bloody delightful. Here are but a few...

First: street signs. The names of the streets of Verona are indicated neither in plastic nor metal, nor by letters painted or printed, but by words engraved in stone. It certainly feels right, as regards the general atmosphere of Verona, but even beyond the context of this city it seems to be a rather beautiful way of displaying street names. Engraved stone almost always looks better — more welcoming, more grounded, more thoughtful — than plastic and metal, does it not?

Second, one can't help but notice the narrow streets of Verona's old town, strung out like a web between the banks of the Adige as an apparently endless labyrinth of alleys and cross-alleys. And yet they do not feel gloomy or dark or dingy. I suspect this has something to do with the weather (bright summer sun) and the design of the buildings, decorated as most of them are with either bricks and tuff or, just as often, marzipan-coloured render. Also, because of their narrowness, Verona's many charming vias are devoid of cars — and what a difference it makes! The noise and pollution and threat of getting run over are gone. Streets are always more pleasant without cars.

Here is a photograph, looking upwards to a thin ribbon of sky, to show you just how narrow some of the streets are. This narrowness is a result of age — we no longer design cities like this, for a variety of reasons. And yet I wonder if many cities would be improved by the character such a compact street-plan can bring to bear, with all its hidden secrets and miniature squares, not to mention the shade one gets from the worst of the midday heat.

Walk along any street in the old town of Verona and cast your eyes upwards. You shall see, crowding round on all sides, an array of balconies — some no more than ledges supported by plain struts, others more pronounced and held aloft by decorated corbels, and always guarded by beautiful iron grilles, and perhaps some grand marble terraces with ornate stone balustrades. And they are, almost all of them, overflowing with flowers and vines. It is a cacophany of miniature delights, for as we walk through Verona there are blossoms and leaves above, and all about us those windows in stone frames with wooden shutters, so often enclosed with delicate, floral ironwork.

It is one balcony in particular, that which apparently abutted the bedroom of Juliet, or Giulietta as she is called locally, that attracts most attention. Very well, but without paying an entry fee you can see balconies equally beautiful — more beautiful! — on every street and tenement in the town. Immense life is brought to Verona by these balconies, flowers, and windows, turning what might otherwise be lifeless blocks into tenements teeming with colour, detail, charm, and character.

So many of the buildings of Verona — the ordinary buildings, I mean, the tenements and apartments, not the palaces and churches — are decorated with fading frescos. Look up and you'll catch the sun-bleached, rain-worn face of a saint peering down at you. The one pictured below is from the 14th century, but rather than being in any way unusual it is only one of hundreds, many of them much larger and most of them similarly damaged, spread beneath the eaves of the houses of Verona.

Two observations. The first is that it ought to remind us of just how religious the Middle Ages were — Christian art was not exclusive to the church alone; people were accustomed to seeing sacred art at all times of day and in all parts of the city. And, secondly, it suddenly struck me when I saw this fresco that, these days, any such image on the side of a building would inevitably be an advert. How strange to see a large picture on the side of a building which hadn't been crafted by an expert to distract me, worm its way into my memory, and influence my behaviour. One wonders how much happier we'd all be if, instead of adverts, it was by art that we were surrounded when walking through our towns and cities.

Postlude

You may have noticed that throughout my brief appraisal of Verona it is to colour and material that I have paid particular attention. This, I think, is almost more important than any discussion about architectural styles and movements. What is it that draws the crowds to Verona, and puts so many wide smiles on the faces of tourists — old and young alike — strolling down its numberless Medieval streets? There is no single answer, of course, because there never is. But, if I were forced to choose one quality above all others, I think it might come in the form of a question: what is Verona made from?

This might sound fatuous, but it really isn't. Notice: each street is paved with marble, tuff, cobbles, or setts, and every street it is lined with buildings of brick, tuff, marble, painted plaster, wood, and ironwork, not to mention all the flowers and frescos. These are all pre-industrial, highly natural materials with richly detailed, varying textures, and warm, changeful, vigorous colours. No plastic cladding here, or tarmac, or plate-glass, or chrome. Verona is proof that when you work with the right materials, and you treat them respectfully and simply, you cannot go wrong. The brick, the marble, the iron, the stone, and the plaster — all have aged remarkably well. Even when peeling, or eroding, and damaged by rain or wind, and rusting, and crumbling, these materials only become more charming, more beautiful, more delightful. There are many cities which could easily glean some highly practical and applicable lessons about urban design from this town.

And so, even though we have no reason to believe Shakespeare visited Verona, I am more inclined than ever, having being there myself, and seen a city which I would cautiously described as noble rather than his preferred fair, to agree with what he has Romeo say upon learning of his banishment:

There is no world without Verona walls,

But purgatory, torture, hell itself.

The last thing upon which I must comment — having said nothing thus far of the food or weather, both sumptuous in the absolute — is the people of the city. For I don't suppose any quantity of Medieval architecture and Roman ruins, however splendid or pure, can be enough to make a city so welcoming, nor so delightful a place to pass several days in contemplation and admiration. Without the Veronese locals — their warmth, charm, and character — the city would not be what it is. To them I say: grazie mille!

Question of the Week

A fortnight ago I asked you:

If you could go back in time to one specific day, which would it be?

Here you were answers:

Dale S

Two answers (sorry...). First, I would like to have been around Christ's tomb on the 3rd day after the crucifixion, for obvious truth verification purposes.I would also have been on Columbus's boat, or perhaps on the shores of Guanahani, when the 3 ships arrived on October 12, 1492. I'm assuming I wouldn't be allowed to intervene, so I won't engage in those alternate history fantasies...I just want to know: what did he really make of it all? Did he really think he was in the East? In the midst of an apocalyptic prophesy? And if I could be allowed to understand the Taíno language, what did the Taínos really think of him?

Charlie B

To treat any day of the past as momentous enough to the point of wishing to travel there would defeat the purpose. The events of any eventful day in history can simply not surpass the mythos that has enshrouded it. To travel back to the day of- for example- Abraham Lincoln’s murder or perhaps the end of any of the countless wars of the past would be ultimately disappointing due to our foreknowledge. Enshrined in the forefront of our minds would be our own contemporary conception of events where we can experience the event simultaneously through a multitude of historical accounts, mapping out the images in our minds much like a film director. Once funnelled through the singular and closed off perception of the individual, the gravitas of the situation would fade out of view, would place in comparison to the fantasy of our mind. Simply put, I would choose to remain in my time, where the fruit of life is ripening by the second, almost ready to drop from the branches. The joys of yesterday are the promises of tomorrow. The past is enriched by the fact that we cannot experience it any longer as direct phenomena. As such, we must continue to fill our days with pure and untamed Life, the endless joyful mundanities and continue to uphold the fluidity of existence.This may not be the answer to your question that you were looking for but nonetheless it is my answer.

Jay M

That’s a tough one after more than 25,000 days. Categories occurred to me for days to relive—or not. In the “not” category are days of “failure,” such as the day on which the quarterback lobbed a downfield pass right in my hands as pass receiver, yet I didn’t catch it. This day is a “not” because I have a hunch the same would occur again if I could go back in time as I was then. To relive “successes,” of which I have had my share, would be nice, yet my remembering them as successes means that they are present enough to me now when I want to revisit them in memory. Then there are memorable instances of kindness or the opposite. To relive an episode of special kindness also would be nice, though somewhat self-congratulatory. This leaves me choosing that I would like to relive any day that is memorable for the opposite of kindness—if I could then do things differently.

Gaspard B

Choosing to go back in time, even for one day, is for me refuting the importance of past experiences : they are experiences, good or bad, but they are also past and should remain as such should they be full of joy or sadness. Simply reliving them or choosing to live them again to change them is denying the importance of the present and the brightness of the future.

As such, going back for one day should *not* be done in a intellectual manner or to reflect on past experiences. To stay focused on present and future, to underline the importance of the present and the futility of reliving the past, this one day in the past should be done with intentions both frivolous and futile.

Having laid such bases, I would go back on a humiliating 5th grade day where I was publicly insulted by a school bully (whom I have not seen or heard of since elementary, and who didn’t bully me neither hard or for long). I would then punch the little shit in the face.

Guillermo E

Me personally? I have always wanted to know what it must have been for Hernan Cortez the first time he gazed at Tenochtitlan, The Mexica Empire city. According to many historians, at the time of Cortez arrival, Tenochtitlan had a population between 200,000 and 250,000 people. By contrast, London had around 60,000 people, Sevilla around 50,000 (Madrid wasn’t even the Capital of Spain yet.) Venice was a mercantile empire with approximately 100,000 people. And Paris was thought to have a population of roughly 225,000. Cortez and his 500 soldiers must have been astounded to encounter the Aztec pyramids. As tall as any European cathedral. A city divided by islands, much like Venice but with twice the population.

Laura W

I take various issues with the notion of time travel. But most importantly here, I feel that the human mind is too often occupied with the memories of the past and the imagination of the future to the detriment of what we actually have: the now.

I would much prefer the ability to spend a single day totally immersed in the present. To be unencumbered with the speculations of tomorrow or yesterday (whether in my own lifetime or beyond) and to wholly live in the moment.

And for this week's question, carrying on from my appraisal of Verona:

What is your favourite city, and why? Feel free to include photographs.

Email me your answers and I'll share them in next week's newsletter.

And that's all

There we have it — another instalment of the Areopagus is concluded, and another format attempted, however erringly, for your interest and use, my Gentle Readers. I hope you can see why I wanted to write about Verona. It was a blessing to have been there, and the least I can do is share what joy I felt in walking its streets and the lessons I learned — the heights to which my heart and mind were called! — in studying its churches, palaces, ironwork, bricks, and many-storied stones. As it was written on the scroll in the arms of the Madonna Verona, a fountain in the Piazza Erbe and an enduring symbol of the town:

EST JUSTI LATRIX URBS HAEC ET LAUDIS AMATRIX

This city, the maiden of justice, hopes for praise

I have done my best! Buona notte one and all; the Areopagus shall return next week.

Yours,

The Cultural Tutor