Areopagus Volume CVI

Seven short lessons every someday.

Welcome one and all to the hundred and sixth volume of the Areopagus. 2026 is three weeks old and a fourth rises hot on its heels. Stormy in England: ceaseless rain, unceasing wind, and slowly ceasing darkness. What will we make of it?

Many of us like to set reading goals at the beginning of each year. Perhaps one per month; possibly (and ambitiously!) one per week. Could mine be among that precious number? Maybe! If not — too bad. But, if only because my book was written with the intention of directing readers to other, much older, much better books, I hope it stands a chance of making your cut.

Also (I should say) this newsletter is fairly long (about nine thousand words) and contains a number of images. As a result it may not appear fully in your email inbox, and will abruptly cut off at some point. This is not an error! You just need to click ‘show full email’ (or something similar, depending on your email provider) to see it all. Alternatively, you can read the full thing on Substack, either the website or app.

All of which leaves just one thing to be said: avanti!

I - Classical Music

Le roi s’amuse III: Scène du bouqet

Léo Delibes (1882)

Performed by the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra

King Francis I of France in the Studio of Benvenuto Cellini by Francesco Podesti (1839)

On 22nd November 1832 a play by Victor Hugo (of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame fame) debuted in Paris. It was called Le roi s’amuse, meaning “The King Amuses Himself’”, and took as its subject King Francis I, who ruled France during the early 16th century. But Francis was not treated kindly by Hugo; the play presents him as an unscrupulous letch. This was interpreted by the authorities as a slight against King Louis Philippe, and so the play was banned after a single performance.

In 1855 Giuseppe Verdi wrote an opera based on Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse, but with a different title (Rigoletto) and altered setting (Renaissance Mantua, instead of Renaissance France). Verdi had censorial troubles of his own, though in his case with the Austrian government, which then ruled northern Italy. Nonetheless (and needless to say) it was a success, and proved popular even (and ironically!) in Paris.

Finally, in 1882, exactly fifty years after its first (and only) performance, Le roi s’amuse was staged again. For this new run a set of incidental music was written by Leo Delibes; ‘incidental music’ is the theatrical equivalent of a film score, i.e. music created to accompany and elevate a performance. Léo Delibes had already written his two great ballets, Sylvia and Coppélia, both of which were hits in their own day and remain popular. It was one year later, in 1883, that he would write the work for which he is most famous: Lakmé, an opera that includes the ubiquitous and eternal aria Dôme épais le jasmin, better known as The Flower Duet.

Delibes’ incidental music for Le roi s’amuse has six parts, plus a reprise of the first, each based on historical musical forms that were popular during the Renaissance (i.e. when the play is set). These are the gaillarde, pavane, lesquercarde, madrigal, and passepied, along with the air that forms its third part, called Scène du bouquet. I think we can hear Delibes having fun with his opportunity to revive and explore Renaissance-style dances; his incidental music for Le roi s’amuse is a kind of miniature Neo-Renaissance masterpiece, and Scène du bouquet is its melodious, supremely moving core. One feels more sophisticated, more lovely, more in love, just listening to it; these are two of the gorgeousest minutes of music ever written.

So, although Léo Delibes wrote what is surely (though competing with Puccini’s Nessun Dorma) the definitive opera aria (insofar as popular culture is concerned), Delibes did not only write The Flower Duet; he was a prolific, popular, fabulously talented composer, and Scène du bouquet is just one of the many other musical fruits his compositional brilliance brought forth.

II - Historical Figure

The Venerable Bede

When the Tuesday before the Ascension of our Lord came, he began to suffer still more in his breathing, and there was some swelling in his feet. But he went on teaching all that day and dictating cheerfully, and now and then said among other things, ‘Learn quickly, I know not how long I shall endure, and whether my Maker will not soon take me away.’ But to us it seemed that haply he knew well the time of his departure; and so he spent the night, awake, in giving of thanks.

That is how a monk called Cuthbert (not to be confused with Saint Cuthbert), writing in the year 735 AD, described the final hours in the life of a man called Bede. Both were monks at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, a monastery in northern England.

Bede was a prolific author, most of whose works have — remarkably! — survived. They include extensive commentaries on the Bible, biographies of various saints or monks, a martyrology, poems, hymns, epigrams, and textbooks on etymology, how to calculate dates, and the art of poetry. These were transcribed, copied, and distributed around Britain and Europe. Bede was a beacon of learning, both secular and religious, famed during his lifetime and afterward for piety and scholarliness. Consequently he was awarded the affectionate epithet of ‘venerable’; in 1899 he was made a saint.

Just one example of his legacy is that Bede popularised the use of Anno Domini (i.e. AD) as a way of dating years. He did not invent it, but Bede’s use of AD — rather than existing methods, such as dating by the regnal year of Byzantine Emperors — was an essential contribution to its rise.

But, of all his works, one stands far above the rest as his most famous and enduring: Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. What is it? A book narrating the history of Britain from its earliest days, through the Roman occupation, the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, and the gradual spread of Christianity, down to his own time. It was dedicated to King Coelwulf of Northumbria and finished in the year 731 AD. Bede died four years later, having just started his final project, which was to translate the Gospels into English. He was buried at Jarrow, but his body — like that of Saint Cuthbert — was moved to Durham Cathedral, where it remains to this day.

I would not recommend Bede’s Ecclesiastical History with the same readiness that I have recommended Jocelyn of Brakelond’s Chronicle of the Abbey of St Edmund’s or the Letters of Heloise and Abelard; as windows into the Middle Ages they are more direct and immediate than Bede.

Nonetheless his great work is worth reading. First (and more narrowly) because it deals with a chapter of history that is uniquely important to northern England. Anybody from that part of the world will have heard of saints like Aidan, Cuthbert, Oswald, or Hilda — Bede fills in those long-established blanks for us, and puts wonderfully clear faces to these familiar but mysterious names. With Bede we also encounter a range of other figures more generally famous in British history: the likes of Alban, Columba, Hengist and Horsa, or Augustine. To understand what England really is, and where it came from, Bede is required reading.

Second (and more broadly) his Ecclesiastical History is worth reading if only to investigate whether he is writing about a world that is recognisably our own. What is the nature of the difference between we of the 21st century and our ancestors, from any part of the world, of past ages? Is it a gulf merely of time, or also of technology?

Though he lived in an age more violent and chaotic than our own, Bede writes with a liveliness and purity of spirit that belie our popular conception of the ‘Dark Ages’ as an era wholly without learning, love, light, or life.

In the preface, where Bede dedicates his work to King Coelwulf and explains that he has written it to be transcribed and distributed more widely, Bede also (and perhaps surprisingly!) explains his sources: ancient writers, more recent scholars, word-of-mouth, and official documents. As he says of a fellow monk called Nothelm:

The same Nothelm, afterwards went to Rome, and having, with leave of the present Pope Gregory, searched into the archives of the Holy Roman Church, found there some epistles of the blessed Pope Gregory, and other popes; and, returning home, by the advice of the aforesaid most reverend father Albinus, brought them to me, to be inserted in my history.

So this was a well-researched book, not idle or fabulous speculation interwoven with mythologies and folk tales. But most surprising is the interconnectedness of the world Bede describes. His Ecclesiastical History includes endless journeys around Europe, especially to and from Rome, whether for the sake of pilgrimage, on official church business, or out of sheer curiosity.

We hear of Aidan who was invited from Ireland to serve as Bishop of Northumbria; of Swidbert who was sent from Northumbria and founded a monastery in Düsseldorf; of Theodore, who was born in Tarsus on the southern coast of modern Turkey, and via Constantinople was sent to Britain by Pope Vitalian, where he became Archbishop of Canterbury; of Willibrord, a Yorkshireman who was made the first ever bishop of the Netherlands under Duke Pepin of the Franks, the great-grandfather of Charlemagne.

Alongside these are endless letters to and from popes, bishops, or kings, and accounts of great congregations at Whitby or Hertford — the synods — organised to decide certain matters, particularly (a gripe and obsession of Bede’s) the true date of Easter.

And, despite our general notion of the Middle Ages (and especially the Early Middle Ages, or Dark Ages) as being ignorant of the ancient world, Bede quotes and references a litany of classical writers, including the likes of Virgil, Pliny, and Josephus. He also begins his Ecclesiastical History with a very precise chronology of the Roman emperors who ruled over Britain, all the way down to the Empire’s collapse, listing Julius Caesar, Augustus, Claudius, Severus, Diocletian, Gratian, and the rest — people we wrongly imagine as forgotten during the Dark Ages.

We do learn of life’s hardships in those long centuries; war and famine, disease and injury, all feature prominently in Bede’s History, though these latter usually in relation to their miraculous cures by bishops, hermits, or holy dust. It is this aspect of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History that the modern reader will find hardest to sympathise with. We are most likely to shake our heads at their credulity, and complacently congratulate ourselves for being so enlightened, so able to penetrate the superstitious illusions of past ages with our sure and scientifically-bolstered knowledge that miracles are impossible. But read Bede’s account of the popular response to the death of Saint Oswald, a pious Northumbrian king who was slain in battle:

How great his faith was towards God, and how remarkable his devotion, has been made evident by miracles even after his death; for, in the place where he was killed by the pagans, fighting for his country, sick men and cattle are frequently healed to this day. Whence it came to pass that many took up the very dust of the place where his body fell, and putting it into water, brought much relief with it to their friends who were sick. This custom came so much into use, that the earth being carried away by degrees, a hole was made as deep as the height of a man.

We no longer use the word ‘miracle’, but our belief in the possibility of certain special substances or particular behaviours that will cure our ailments and improve our lives remains undiluted. I am not referring to modern medicine; I mean the essentially endless procession of new (and very trendy) habits, products, or ingredients, that daily sweep the internet and soon thereafter our streets. It isn’t so much the things themselves (although plenty of our modern methods and habits are no more ‘scientifically proven to work’ than saints’ relics!) as the way we believe in them, that I’m talking about. Was the belief of Bede’s contemporaries in the benefits of dust stained with Saint Oswald’s holy blood so different from our belief in the possibility that some new product, revealed to us by cutting-edge marketing or lifestyle influencers, will finally solve our problems?

Bede also describes how, in the process of Christianising Britain, missionaries were urged to adopt pagan sites, refitting temples as churches and even adopting and adjusting their rituals, like animal sacrifice. We are frequently told that various Christian celebrations, especially their dates, are linked to ancient pagan ways; Bede, quoting a letter from Pope Gregory, explains how and why this happened. So this is not a purely idealised history; Bede offers plenty of political and historical realism.

…the temples of the idols in that nation ought not to be destroyed; but let the idols that are in them be destroyed; let water be consecrated and sprinkled in the said temples, let altars be erected, and relics placed there. For if those temples are well built, it is requisite that they be converted from the worship of devils to the service of the true God; that the nation, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may remove error from their hearts, and knowing and adoring the true God, may the more freely resort to the places to which they have been accustomed.

…to the end that, whilst some outward gratifications are retained, they may the more easily consent to the inward joys. For there is no doubt that it is impossible to cut off every thing at once from their rude natures; because he who endeavours to ascend to the highest place rises by degrees or steps, and not by leaps.

And remember: at this point in time there was no such thing as England. The country we now call by that name was divided into multiple, frequently warring, variously Christian or pagan kingdoms. Here, narrating the Council of Hatfield, Bede lists them: Egfrid of the Northumbrians, Ethelred of the Mercians, Aldwulf of the East Angles, and Hlothere of Kent.

In the name of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, under the rule of our most pious lords, Egfrid, king of the Northumbrians, in the tenth year of his reign, the seventeenth of September, the eighth indiction; Ethelred, king of the Mercians, in the sixth year of his reign; Aldwulf king of the East Angles, in the seventeenth year of his reign; and Hlothere, king of Kent, in the seventh year of his reign…

The theme of Bede’s book might well be progress, a national journey from disunity to unity, primarily religious but also political. He died before England became a single kingdom, but Bede recorded the events that preceded and paved the way for it. We learn, in particular, that the Church was a unifying force, both culturally and politically; though kings were rival rulers, bishops were united, serving together under their most senior, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and beyond him the Pope in Rome.

Nonetheless, Bede does not shy from criticising his beloved Church; in particular he was uncomfortable with the lavish lifestyle of certain bishops, and wherever he knew of priests derogating from their duties he said so:

…even our Lord’s own flock, with its shepherds, casting off the easy yoke of Christ, gave themselves up to drunkenness, enmity, quarrels, strife, envy, and other such sins.

We in the 21st century might believe partisanship has grown worse of late, and that our relationship with the truth more strained than ever; Bede, like so many historians, seems to describe precisely the same problem:

…the island began to abound with such plenty of grain as had never been known in any age before; along with plenty, evil living increased, and this was immediately attended by the taint of all manner of crime; in particular, cruelty, hatred of truth, and love of falsehood; insomuch, that if any one among them happened to be milder than the rest, and more inclined to truth, all the rest abhorred and persecuted him unrestrainedly, as if he had been the enemy of Britain.

His Ecclesiastical History can be funny at times, unintentionally or not, especially thanks to Bede’s personal bugbear. We all have one; his was calculating the date of Easter, even bringing it up when praising the otherwise universally loved Aidan:

I have written thus much concerning the character and works of the aforesaid Aidan, in no way commending or approving his lack of wisdom with regard to the observance of Easter; nay, heartily detesting it, as I have most manifestly proved in the book I have written, De Temporibus.

Meanwhile this is what he says of the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons:

In a short time, swarms of the aforesaid nations came over into the island, and the foreigners began to increase so much, that they became a source of terror to the natives themselves who had invited them.

It is a strange and striking world that Bede preserved for us, a world of miracles, holy deeds, pious or violent kings, deposed princes, politically prudent marriages, wise and eccentric nuns, lonely churches of wood with beams impervious to fire, vast stone monasteries on distant peninsulas, pedantic ecclesiastical disputes, lengthy explanations of how to calculate dates, letters from popes, perilous journeys through hostile lands, the declarations of great synods, hermits living on lake-islands, vivid descriptions of Hell and Heaven, including the destruction of the World and a proto-Dantean vision of the afterlife, accounts of the distant Holy Land, of the churches at the Sepulchre and Golgotha, shepherds cured of blindness by saints, and genuinely touching accounts of friendship, as of Cuthbert and Herebert.

There are also moments of quite lyrical magnificence in his Ecclesiastical History, most famously the parable of the sparrow, as told at a great congregation called by King Edwin of Northumbria to discuss adopting the Christian faith:

The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all.

We learn of the origins of church music, emerging at a time when — unlike ours! — there was not unceasing sound and song wherever people went; trained singers, few and far between, brought this fabulous art with them:

The Abbot John did as he had been commanded by the Pope, teaching the singers of the said monastery the order and manner of singing and reading aloud, and committing to writing all that was requisite throughout the whole course of the year for the celebration of festivals; and these writings are still preserved in that monastery, and have been copied by many others elsewhere. The said John not only taught the brothers of that monastery, but such as had skill in singing resorted from almost all the monasteries of the same province to hear him, and many invited him to teach in other places.

In another famous chapter we learn of Caedmon, England’s first poet — the first to compose poetry in the vulgar tongue, then Old English, rather than Latin — and how he received his gift. An elegant and moving story:

…he had never learned anything of versifying; and for this reason sometimes at a banquet, when it was agreed to make merry by singing in turn, if he saw the harp come towards him, he would rise up from table and go out and return home.

Once having done so and gone out of the house where the banquet was, to the stable, where he had to take care of the cattle that night, he there composed himself to rest at the proper time. Thereupon one stood by him in his sleep, and saluting him, and calling him by his name, said, “Cædmon, sing me something.” But he answered, “I cannot sing, and for this cause I left the banquet and retired hither, because I could not sing.” Then he who talked to him replied, “Nevertheless thou must needs sing to me.” “What must I sing?” he asked. “Sing the beginning of creation,” said the other. Having received this answer he straightway began to sing verses to the praise of God the Creator, which he had never heard.

Bede’s is a history told robustly and affectionately, aware of political realities but believing forthrightly in the possibility of purity on Earth, with a cast that is both wide and deep; it is, above all, a deeply, deeply, deeply Medieval book.

Who was Bede? He tells us at the conclusion of his history (which is where he also provides a list of all the other works he has written): a simple and scholarly monk who loved his books and who does not seem to have ever left northern England.

Having been born in the territory of that same monastery [Monkwearmouth-Jarrow], I was given, by the care of kinsmen, at seven years of age, to be educated by the most reverend Abbot Benedict… and spending all the remaining time of my life a dweller in that monastery, I wholly applied myself to the study of Scripture; and amidst the observance of monastic rule, and the daily charge of singing in the church, I always took delight in learning, or teaching, or writing.

For our final words we turn to Bede himself, included at the end of his dedication to Coelwulf; a humble request from a man who did so much for his own age and people, and who continues to serve us now, well over one thousand years later:

I beseech all men who shall hear or read this history of our nation, that for my infirmities both of mind and body, they will offer up frequent intercessions to the throne of Grace. And I further pray, that in recompense for the labour wherewith I have recorded in the several provinces and more important places those events which I considered worthy of note and of interest to their inhabitants, I may for my reward have the benefit of their pious prayers.

All quotes are from A.M. Sellar’s translation of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History.

III - Art

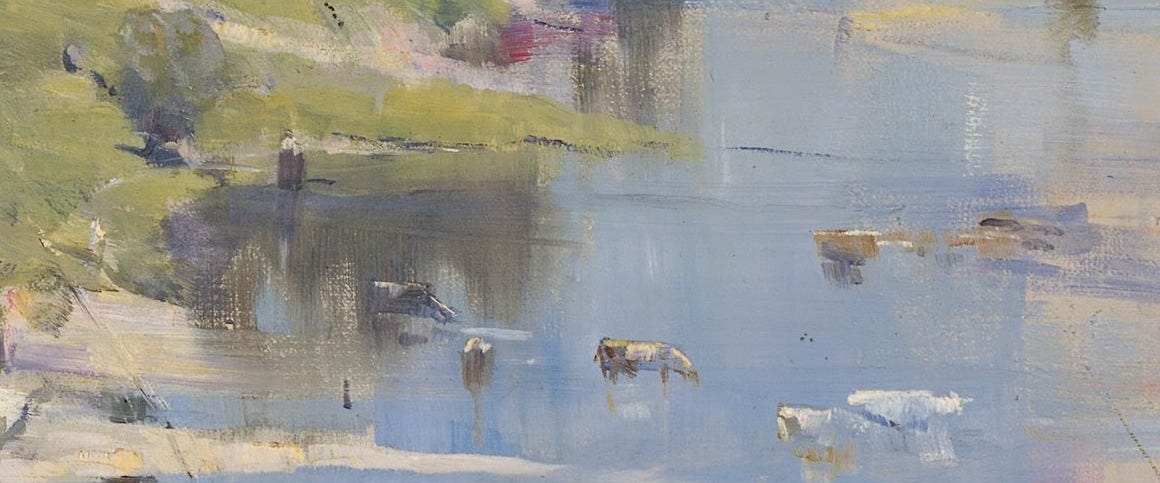

The purple noon’s transparent might

Arthur Streeton (1896)

I have two things to say about this painting. First: Arthur Streeton (who painted it) was a member of the Heidelberg School. This was an art movement, or really (at the time) a specific group of painters who originally gathered at a suburb of Melbourne called Heidelberg (hence their name). They have also been called the Australian Impressionists, and this is accurate; it was Streeton and his contemporaries who first, if not quite brought to Australia, then fulfilled and embodied, the avant-garde methods and ideas of the French Impressionists.

And so what’s fascinating about the Heidelberg School, beyond the intrinsic loveliness of their paintings, is that we see a familiar artistic approach reapplied in a different context; rather than the cypresses of southern France or boulevards of Paris portrayed in broad brushstrokes and blue-backed colours smudging together, it is (in the particular case of The purple noon’s transparent might) the cattle, eucalyptus trees, and windpumps of the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales.

The second thing to comment on is this painting’s name, an ideal case study for the art of titling. Titles are strange. They aren’t part of the work — one could watch a film, read a book, or look at a painting without knowing its name — and yet, if we do know a title, it affects how we think and feel. Titles direct our attention by selecting a particular character, place, or idea; Hamlet is about Hamlet, for example, and Wuthering Heights is set in Wuthering Heights. But they can also be misleading, or metaphorical, and entirely reframe what a given work of art would otherwise seem to be about. Julius Caesar only speaks only 135 lines in the eponymous play; is he really the ‘main’ character? Joseph Conrad’s choice of Heart of Darkness for the title of his most famous book has surely contributed to its success; the book is masterful regardless of what we call it, but that title throws up so many questions (most obviously: “what is the ‘heart of darkness?’”) and lends the book a kind of scriptural or mythical quality. They are extraneous to an artwork but also inseparable. Even when an artist refuses to give their work a title, that itself is a choice which shapes how we view it; things have to have names, otherwise we can’t actually talk about them.

And so Streeton’s rather unusual title forces us, even against our will, to look at the painting differently. What is ‘transparent might’? The title is actually a line by the English poet Percy Shelley, writing in 1818. Will Shelley’s poem give us further clues to Streeton’s intention? Here’s the full stanza from which that line is taken:

The sun is warm, the sky is clear,

The waves are dancing fast and bright,

Blue isles and snowy mountains wear

The purple noon’s transparent might,

The breath of the moist earth is light,

Around its unexpanded buds;

Like many a voice of one delight,

The winds, the birds, the ocean floods,

The City’s voice itself, is soft like Solitude’s.

So far, so good; Shelley is describing the serenity of a coastal scene. Are we to think this was all Streeton had in mind, taking for his subject nothing more than the beauty of midday, though with an Australian rather than (as Shelley had written) European setting? We read on:

Alas! I have nor hope nor health,

Nor peace within nor calm around,

Nor that content surpassing wealth

The sage in meditation found,

And walked with inward glory crowned—

Nor fame, nor power, nor love, nor leisure.

Others I see whom these surround—

Smiling they live, and call life pleasure;

To me that cup has been dealt in another measure.

After portraying an essentially perfect spring day on the outskirts of a splendid seaside city, and having described his landscape without any metaphorical embodiment of anything other than emotional peace and spiritual serenity, Shelley plunges into absolute and unrelenting, though highly composed, misery. Does this change our view of Streeton’s The purple noon’s transparent might?

After all, Shelley called his poem Stanzas Written in Dejection, near Naples. Are we then to search for notes of sadness, of dejection, in Streeton’s idyllic landscape? Maybe! But whatever its potentially hidden implications, without the title Streeton gave it we wouldn’t have been inclined (I think) to look for them. Perhaps his whole intention was to force us into a strange quest of hunting for dejection in a landscape ostensibly devoid of it, and even conjuring it in our imaginations despite having no real basis in the painting itself. Small details lead us on; we search for a solitary onlooker.

Maybe none of these theories hold water; perhaps Streeton chose that line simply because it captured something of his homeland’s nature, and thought nothing of Shelley’s wider poem; perhaps his intention was to place Australian arts, and the nation itself, on a level with the lauded arts of western Europe, casting Shelley as a kind of welcome rival. Or could it have been ironic? Maybe it’s all a ruse, and Streeton hardly thought of it, and wanted to lay traps for future interpreters.

Streeton did comment on the painting’s formulation, recalling the extreme heat of the two days he painted it — a heat, through Streeton’s skill, we experience: one feels a sheen of sweat on the forehead just looking at those shrivelled shadows, glassy waters, and baking blue hills — and his obsession with Shelley at the time. Nonetheless he did not directly explain the painting or its title; that is a delightful riddle for us, a hundred and thirty years later, to solve. Streeton could have called it Hawkesbury River at Noon and left it there; he did not, and we may thank him for it!

IV - Architecture

Crespi d’Adda

A little less than ten miles south-west of Bergamo, in northern Italy, lies a peculiar town with a peculiar name: Crespi d’Adda. Its peculiar name explains its peculiar nature: Adda, for the name of the river along which it was built, and Crespi, for the industrialist — Cristoforo Benigno Crespi — who built it.

Construction started in 1878, with a cotton mill and large blocks for the first workers to live there. But when Cristoforo Crespi’s son — Silvio — took over in 1889, the town was redeveloped and improved. As he explained:

The system of building large, multi-storey houses, capable of housing ten or even twenty families, was a mistake. They were built like barracks, not homes.

And so individual homes were built for each working family instead, with larger houses for the foremen, and quite luxurious villas for managers. By 1910 there was also a school, church, hospital, hotel, theatre, sports field, cooperative, and club — all owned and run by the company.

This sounds remarkable, but it wasn’t unusual; the late 19th century was the Golden Age of ‘company towns’. These were settlements built for and populated entirely by the workers of a given company, which then managed all town affairs.

Some succeeded; many failed. They had their problems, both in terms of urban design and how they were managed, but they also represented some of the earliest attempts at total, cohesive, modern town planning, and at improving the previously miserable living conditions of factory workers. These 19th century industrialists took it upon themselves to provide everything for their employees… including their moral codes! Certain behaviours were encouraged or dissuaded, and the Damoclesian sword of being fired (and therefore also losing one’s family home) gave employers immense and surely troubling power over the employees who lived in these company towns.

So Crespi’s relationship with the people who worked for him retained the framing of the lord-vassal bond that defined the Middle Ages (and preindustrial world more generally), whereas our current idea of the employer-employee relationship has cast off that framing almost entirely. To restate that sentence in a less abstract way, and as an example of what I mean, consider this fabulous structure:

It dominates Crespi d’Adda; what is it? The summer residence of the Crespi family. Much as Medieval lords lived in manors or castles, and as their vassals worked the land around these strongholds, Crespi chose to build himself a Neo-Gothic mansion at the heart of his industrial town, complete with the swallow’s tail crenellations and banded red bricks of Medieval Lombardic architecture.

One’s landlord and employer being the same person does not sound ideal; but, if ours is an era where those who run our biggest corporations seem further removed from their employees than ever, there is at least something interesting about the idea of a CEO living in the midst of those who work for them, and the idea that such a CEO might feel obliged (as Crespi did) to provide clean, affordable, and quite lovely housing, alongside everything else needed for a decent life.

Still, this castle is not quite the most striking structure in the town; that is surely the cotton mill itself, which encapsulates the long-forgotten 19th century idea that a building’s purpose needn’t restrict or even relate to its appearance:

Nearby is another work of industrial eclecticism, the Taccani Hydroelectric Power Plant, built in 1906 to provide energy for the town and its mill; this, too, has been designed with the same decorative delight one would normally expect of a palace or grand public building. These days we think that industrial buildings, whether cotton mills or hydroelectric power plants, are necessarily boring at best, though ugly as a rule; Crespi d’Adda is surviving proof that it needn’t be so.

Crespi sold the town in 1929 and thereafter it changed ownership several times, with much of the housing sold off privately, until the cotton mill finally closed in 2004; the power plant remains operational, however, and Crespi d’Adda is still inhabited. The town and its complex of buildings became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995, primarily for how cohesively they encapsulate the lost age of company towns.

One could take a cynical view of Crespi d’Adda, and of the whole 19th century culture of industrial paternalism; nonetheless, and even taking into account any and all rightful criticisms of Crespi’s ilk, there is much we might learn. No age is purely good; no age is purely bad. The work of history is to discern one from the other, and to investigate whether we can learn from the former without risking the latter.

V - Rhetoric

Questions in the Time of the Internet

The wisdom literature of all the nooks and ages of the world has lots in common. Regular observations on universal flaws or features of the human condition reoccur across monotheistic, polytheistic, ancient, and modern religions or mythologies. These observations are usually paired with or take the form of advice: better do this; better not do that.

One of these recurring themes is the difficulty of speech. Not the art of rhetoric itself, or the necessity and use of becoming skillful in speech. Rather, I mean the more troubling matter of when and when not to speak, of when to ask questions and when not to, of when to answer or even refuse to answer. It has been said we live in a time of informational overload; the Internet is ubiquitous, essentially infinite, and brutally addictive. We want and think we need to know so many things: we are Googling all the time, and now we are asking various incarnations of AI a thousand million questions every minute of the day. But we must be careful; our ancestors can help.

If we had no limits of time or effort, it wouldn’t matter what we ask. We’d have time to ask every single possible question, and follow-up question, until everything we needed or wanted to know had been revealed, and we understood it all. But we do have limits of both time and effort! Ergo we cannot ask everything. What we do ask, then, better be worth asking; what we respond to better be worth responding to.

The wisdom-poetry of Norse mythology treats knowledge itself as a magical thing, symbolised by Odin’s mastery of runes — in other words, writing itself! — and therefore also of spells. But this quite sublime symbolism is presented alongside very straightforward, very practical, and altogether timeless advice. Not least, from the 10th century Hávamál, that the less we say, the wiser we seem:

In mockery no one | a man shall hold,

Although he fare to the feast;

Wise seems one oft, | if nought he is asked,

And safely he sits dry-skinned.

To say less (and listen instead) is usually best:

A witless man, | when he meets with men,

Had best in silence abide;

For no one shall find | that nothing he knows,

If his mouth is not open too much.

(But a man knows not, | if nothing he knows,

When his mouth has been open too much.)

The great Thomas à Kempis, quoted before in the Areopagus and frequently in my book, had much to say here. He was a 15th century Dutch priest who wrote a kind of spiritual guidebook called the Imitation of Christ. Throughout, he repeatedly warns against the danger of unnecessary questions, of questions that distract us from what is actually useful and meaningful in life:

Woe unto them who inquire into many curious questions from men.

And:

Blessed is the simplicity which leaveth alone the difficult paths of questionings

Or, most simply and brilliantly of all:

Leave curious questions.

Some of this was meant in a very particular historical context; Thomas à Kempis rejected the triflingly complex, altogether pedantic theological and ecclesiological disputes that defined the Middle Ages and seemed, in his time, to be doing more harm than good for the Catholic Church:

And be not given to inquire or dispute about the merits of the Saints, which is holier than another, or which is the greater in the Kingdom of Heaven. Such questions often beget useless strifes and contentions: they also nourish pride and vain glory, whence envyings and dissensions arise, while one man arrogantly endeavoureth to exalt one Saint and another another.

But his observations of what is good for humankind exceed that context; his Imitation of Christ is timeless. Here, and again, contrasting our limited time on Earth with the overwhelming multitudes of things we might ask about or seek to understand, he urges us to pursue what is obviously and actually worth knowing:

Our own judgment and feelings often deceive us, and we discern but little of the truth. What doth it profit to argue about hidden and dark things, concerning which we shall not be even reproved in the judgment, because we knew them not? Oh, grievous folly, to neglect the things which are profitable and necessary, and to give our minds to things which are curious and hurtful! Having eyes, we see not. And what have we to do with talk about genus and species!

This passage is reminiscent of a famous parable told by the Buddha, of a man struck by a poisoned arrow, in the Cūḷamālukya Sutta. It is lengthy, but worth reading:

Suppose a man was struck by an arrow thickly smeared with poison. His friends and colleagues, relatives and kin would get a surgeon to treat him. But the man would say: ‘I won’t extract this arrow as long as I don’t know whether the man who wounded me was an aristocrat, a brahmin, a peasant, or a menial.’

He’d say: ‘I won’t extract this arrow as long as I don’t know the following things about the man who wounded me: his name and clan; whether he’s tall, short, or medium; whether his skin is black, brown, or dingy; and what village, town, or city he comes from. I won’t extract this arrow as long as I don’t know whether the bow that wounded me was straight or recurved; whether the bow-string is made of swallow-wort fibre, sunn hemp fibre, sinew, sanseveria fibre, or spurge fibre; whether the shaft is made from a bush or a plantation tree; whether the shaft was fitted with feathers from a vulture, a heron, a hawk, a peacock, or a stork; whether the shaft was bound with sinews of a cow, a buffalo, a black lion, or an ape; and whether the arrowhead was spiked, razor-tipped, barbed, made of iron or a calf’s tooth, or lancet-shaped.’

That man would still not have learned these things, and meanwhile he’d die.

Just because we can know something doesn’t mean we should spend our time trying to know it; not all knowledge is equally valuable in the hunt for emotional contentment, spiritual peace, and intellectual satisfcation. Time is precious.

Buddhist scripture has more to offer; no world religion or philosophy places such emphasis on this particular problem. The Pañha Vyākaraṇa Sutta, for example, describes the four ways of asking questions. Note the fourth:

Monks, there are these four ways of answering questions. What four? There is a question that should be answered categorically. There is a question that should be answered analytically. There is a question that should be answered with a counter-question. There is a question that should be set aside.

Or, in the alternative formulation of Sir John Falstaff, from Henry IV Part I:

Shall the blessed sun of heaven prove a micher, and eat blackberries? A question not to be asked. Shall the son of England prove a thief, and take purses? A question to be asked.

And we hear it again in the Old Testament, in the Book of Proverbs:

Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest thou also be like unto him.

There is also Gilgamesh — the hero of the eponymous Sumerian legend, humanity’s first and oldest epic, composed some four thousand years ago or more — who seeks the secrets of eternal life after seeing his friend die. He goes in search of a man called Utnapishtim, the only human to have been blessed by the gods with immortality:

“I have come on account of my ancestor Utnapishtim, who joined the Assembly of the Gods, and was given eternal life. About Death and Life I must ask him!”

He finds Utnapishtim, who speaks to our hero:

“Gilgamesh, you came here exhausted and worn out. What can I give you so you can return to your land? I will disclose to you a thing that is hidden, Gilgamesh, I will tell you.”

Utnapishtim says that he will reveal the secret of eternal life to Gilgamesh if he can stay awake for seven days and seven nights. Gilgamesh falls asleep; how can he hope to conquer death if he cannot conquer sleep? Gilgamesh must die, and his pursuit of immortality has only increased his burden. Gilgamesh asked himself whether immortality was possible; he would have been happier, taking the advice of the Buddha or Thomas à Kempis or Odin, to leave that question unanswered.

It is a strange truth echoed in another passage from the Hávamál:

A measure of wisdom | each man shall have,

But never too much let him know;

For the wise man’s heart | is seldom happy,

If wisdom too great he has won.

Icelandic mythology, Sumerian legend, Buddhist parables, Medieval priests, Hebrew scripture, and Shakespeare; these we have surveyed, but one fountain of wisdom remains: the 2004 science fiction thriller I, Robot. Although I don’t suppose it counts as ‘wisdom literature’, cinema is surely the modern equivalent of ancient mythology, and one line from that film has always stayed with me. Perhaps you will recognise and remember it also:

That, detective, is the right question.

The Internet contains many things, but most of what it contains will do us no good; our ancestors, from all corners of the Earth, knew this, and we would be wise to heed their wisdom when the false promise of unbounded knowledge is more alluring, more readily available, than ever before.

VI - Writing

The Ring and the Book

In 1860 Robert Browning came across a very old book at a flea market in Florence; it was bound in yellow leather and contained a set of legal documents relating to a strange and scandalous case dating to the year 1698. Browning read these documents and they fired his imagination — so he wrote a kind of epic poem based on what he affectionally called this ‘Old Yellow Book’. It runs to 21,000 lines, divided into twelve parts, and is usually described (fairly, I suppose!) as a ‘verse novel’ rather than a straightforward epic poem; epic in length, but essentially domestic in subject.

Told briefly, the case concerned the alleged murder of a woman called Pompilia, along with her parents, by the nobleman Count Guido Franceschini, to whom she had been married; involved in this case were also a priest, Caponsacchi, who had helped Pompilia flee Count Guido and may have been her lover, and even Pope Innocent XII, to whom this case was referred. Among its myriad problems were the question of Pompilia’s birth (had the Comparinis, her alleged parents, adopted her?) and a trove of supposed letters exchanged between Pompilia and Caponsacchi, plus the contents of various wills, original motivations for the marriage, and obscure legal precedents.

Without dwelling on the poem itself (though a day may come!) what I find most instructive about its conception is Browning’s decision not to narrate the whole story from his or another single perspective, but to give each major character their own hearing, their own chance to make a case for themselves.

We begin with Browning himself, explaining how he found the Old Yellow Book and why he decided to turn its contents into a verse novel; then we hear from the citizens of Rome, both those for Pompilia and for Guido, from a lawyer not involved in the case, from Count Guido, from the priest Caponsacchi, from Pompilia, from two lawyers (both the prosecution and defence), from Pope Innocent XII, from Guido once again, and finally from Browning on the other side of his work.

We can read the materials that inspired Browning’s poem; the Old Yellow Book is available online (here)! There’s something thrilling and revealing about going straight from those torturously detailed, intermingling and inconsistent legal accounts and arguments, to Browning’s majestic poem, and wondering how we might have done the same. Could we have imagined such a story, given the same source material?

But, more to our point, the fact is that Browning tells the same story ten times from nine points of view (Guido’s point of view is given twice, though at different stages in the narrative), plus a prologue and epilogue from his own perspective, on either side of his Herculean effort. In other words… he wrote the same story twelve times over! Each part brings with it new or alternative facts, changed arrangements of narrative, differing emphases, and divided worldviews; at no point do we feel we’ve heard it all before, and I (for one) found my sympathies adjusting with every new chapter I read.

The Ring and the Book teaches, among many other things, that we can’t and perhaps even shouldn’t only write things once over. A story told is not a story finished; any given way of telling a story is only one of thousands, and we would be fools not to search out those other ways. Writing the same thing again — a story, an essay, whatever it is — forces you to actually inhabit the mindset, emotional landscape, and worldview of other people. Told but once, we can complacently believe we are telling a story (or explaining a set of faces or ideas) from either an objective or alternative point of view. Only when we have to rewrite that same narrative from a different perspective do we realise that we were, all along, telling it as ourselves, neither objectively nor alternately.

VII - The Seventh Plinth

What never changes?

There’s a saying that “some things never change,” or the old-fashioned French version usually shorted to “plus ça change”, from “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”, meaning “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” I think this is pretty much true, and few things are more heartening or humanely amusing than to find what feel like modern stereotypes in old books. The way Erasmus described being a student in the 1490s, and the way Victor Hugo describes students in both Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, are essentially indistinguishable from how we think of students now: shabbily dressed, full of idealistic and unrealistic ideas about society, and totally penniless but always somehow drunk nonetheless.

The French Renaissance poet Joachim du Bellay (born in 1522; died in 1560) provides us with another five-hundred-year-old case of plus ça change. It’s the fifteenth poem of a collection called Regrets, written during three miserable years in Rome, when all he could do was think of home.

You’d like to know, Panjas, how I spend my time?

I think about tomorrow and its expense,

How, without cash in hand, I can finance

A hundred debts contracted in my name.

I go, I come, I run, I waste no time,

I court a banker for a small advance;

One debtor fixed, another tries his chance;

I don’t pay out a quarter of their claims.

Now here’s a letter, an account, a bill;

Tomorrow’s the consistory with still

More news to cause a headache, if not worse.

Here there’s clamour — protests, shouts, and cries;

Tell me, my Panjas, are you not surprised

At how, despite all that, I’m writing verse?

A penniless artist! A ‘creative’ (as we call them now) struggling to find financial stability! A sulking poet moaning that the economy has no place for him! Have we not heard this before, perhaps even met such a person or read such an article lamenting such a situation this very day? I think so. Plus ça, and all that.

Walter Pater’s exquisite The Renaissance (published, to shock and awe, in 1873) contains a chapter on Joachim du Bellay. As an art critic and art historian Pater is sort of like the Anti-Ruskin. To talk as Pater himself talked, Pater as a critic is like a pearl-fisher, who has fished his exquisite little pearls from the hidden corner of a bay otherwise well-populated by swimmers and fishermen, and presents them to us without judgment or explanation; Pater gives elegant, obscure, almost purely symbolistic, but utterly convincing impressions of particular artists — that is, compared to John Ruskin’s absolute precision of description and explanation, his actual scholarly interest in and knowledge of the material world (botany, minerology, meteorology), and (of course) the ubiquitous lodestar of his moral logic.

Had F. Scott Fitzgerald been an art critic, he would have written like Pater; had Pater commented on Fitzgerald, he would have said (perhaps) that, “he was a man who had perfected the rare but very melancholy art of writing in nothing but mondegreens.” Or maybe not! Both were writers who forged sweeping but convincing characterisations of humanity or human behaviour from the minutest observations, and presented them in highly imagistic, very allusive, very delicately and carefully wrought sentences.

This is what Pater says about du Bellay:

Much of Du Bellay’s poetry illustrates rather the age and school to which he belonged than his own temper and genius… its interest depends not so much on the impress of individual genius upon it, as on the circumstance that it was once poetry a la mode, that it is part of the manner of a time—a time which made much of manner, and carried it to a high degree of perfection. It is one of the decorations of an age which threw much of its energy into the work of decoration. We feel a pensive pleasure in seeing these faded decorations, and observing how a group of actual men and women pleased themselves long ago.

Pater is correct. The chief pleasure of reading Joachim du Bellay is to learn about his time and society; but, when we find him versifying his financial struggles as an artist, we realise that we are reading about a society that, despite what we are taught and led to believe, remains recognisably our own, and that it was one inhabited, for all that was different in it, by people of precisely the same sort as you and me.

Pater delineates himself in this way, and does not fail to identify what is special in du Bellay rather than merely of his age; though du Bellay is a pristine aesthetic mirror to the spirit of Renaissance France (before the Wars of Religion), he also achieved a personality revealed through that aesthetic:

But if his work is to have the highest sort of interest, if it is to do something more than satisfy curiosity, if it is to have an aesthetic as distinct from an historical value, it is not enough for a poet to have been the true child of his age, to have conformed to its aesthetic conditions, and by so conforming to have charmed and stimulated that age; it is necessary that there should be perceptible in his work something individual, inventive, unique, the impress there of the writer’s own temper and personality.

The above-quoted poem, from Joachim du Bellay’s Regrets, and much like the rest of those fabulous Regrets, represents what is individual in him, his own true temper, even if it has been expressed in the trappings of his times. He was a funny man:

I hate the Florentine’s greed and usury,

I hate the thick slow-witted Sienese,

I hate the lying tongues of Genoese

And cold Venetian ways, hostile and sly.

I hate Ferrara folk (don’t ask me why)

And Lombards who break any oath they please,

Fat lazy Romans, lolling at their ease,

Neapolitans puffed up with vanity.

I hate the rowdy English and the Scotch,

Burgundian traitors, French who talk too much,

The haughty Spaniard and the drunken German.

I short, I hate some vice in every nation,

I hate myself for all imperfection,

But most of all I hate pedantic learning.

Or, more straightforwardly:

You don’t believe in God? Something much worse:

That you’re a pedant; that’s the crowning vice.

But he was not misanthropic or cynical; when du Bellay rails against Rome it is always, if not tongue-in-cheek, then highly self-aware; not inauthentic (really quite shocking, at times, for its plainness!) but quite forgiving, and simultaneously self-critical. Do you get the same feeling from his poetry? I hope so.

If I frequent the Vatican, I see pride

And secret vice disguised by ceremony,

The martial noise of drums, strange harmony,

And scarlet prelates, splendidly arrayed.

Du Bellay was not only funny, and not only a talented complainer; he was also capable of refined and sincere expressions of love, especially of that peculiar, essentially self-imposed or sought-after suffering-in-longing so typical of Renaissance sonneteers: the likes of Ronsard, Spenser, Sidney, and (the original) Petrarch. This comes from du Bellay’s sonnet sequence, very different to his Regrets, called The Olive:

If our whole life be less than one short day

In time eternal, if each turning year

Takes in its course the days that come no more,

If all that’s born is destined to decay,

Why do you love the darkness of our day,

My dreaming soul, imprisoned as you are,

When to a brighter dwelling you might soar

With such wide wings to bear you far away?

What unites his life and poetry and satire is world-weariness; du Bellay’s verse resonates with a serious, self-aware melancholy, with a Byronic Weltschmerz two and a half centuries before Byron was born. From du Bellay’s Antiquities of Rome, a collection of poetic meditations on the ruins of the Roman Empire:

Newcomer, eager to find Rome in Rome

And finding there’s no Rome in Rome to see,

Old palaces, this crumbling masonry

Of walls and arches, that’s what men call Rome.…

Rome is the only monument to Rome,

And Rome by Rome alone was overcome.…

So, step by step, did Rome’s great empire grow

Until Barbarians who laid it low

Left only ancient ruins free for all

To pillage, like poor fellows that are seen

Stepping behind the harvester to glean

Whatever careless remnants he lets fall.

We can see why Pater chose du Bellay for one of the select few artists to be studied in The Renaissance; he had a certain sensibility, and what we might call a forwardness of perspective — du Bellay’s poetry contains much that was true of the Renaissance more generally, and (vitally) contains much that would become true in future ages.

But I’m getting away from things; the Areopagus is winding ineluctably down, and January must have its way.

All translations of Joachim du Bellay by Anthony Mortimer.

And that’s all

In the final section of Robert Browning’s The Ring and the Book, where he returns to his own perspective as the author of this verse novel, reflecting on why and how he has written it, he says:

What was once seen, grows what is now described,

Then talked of, told about, a tinge the less

In every fresh transmission; till it melts,

Trickles in silent orange or wan grey

Across our memory, dies and leaves all dark,

And presently we find the stars again.

Follow the main streaks, meditate the mode

Of brightness, how it hastes to blend with black!

A tinge the less in every fresh transmission. Gallingly, gruesomely, gorgeously truthful… and terribly sad! What is the Areopagus if not things seen, grown described, talked of, and (finally) told about? Well: I hope to have stemmed that trickling in silent orange or wan grey, and restored the faintest flicker of brightness’ first mode.

Yours,

The Cultural Tutor