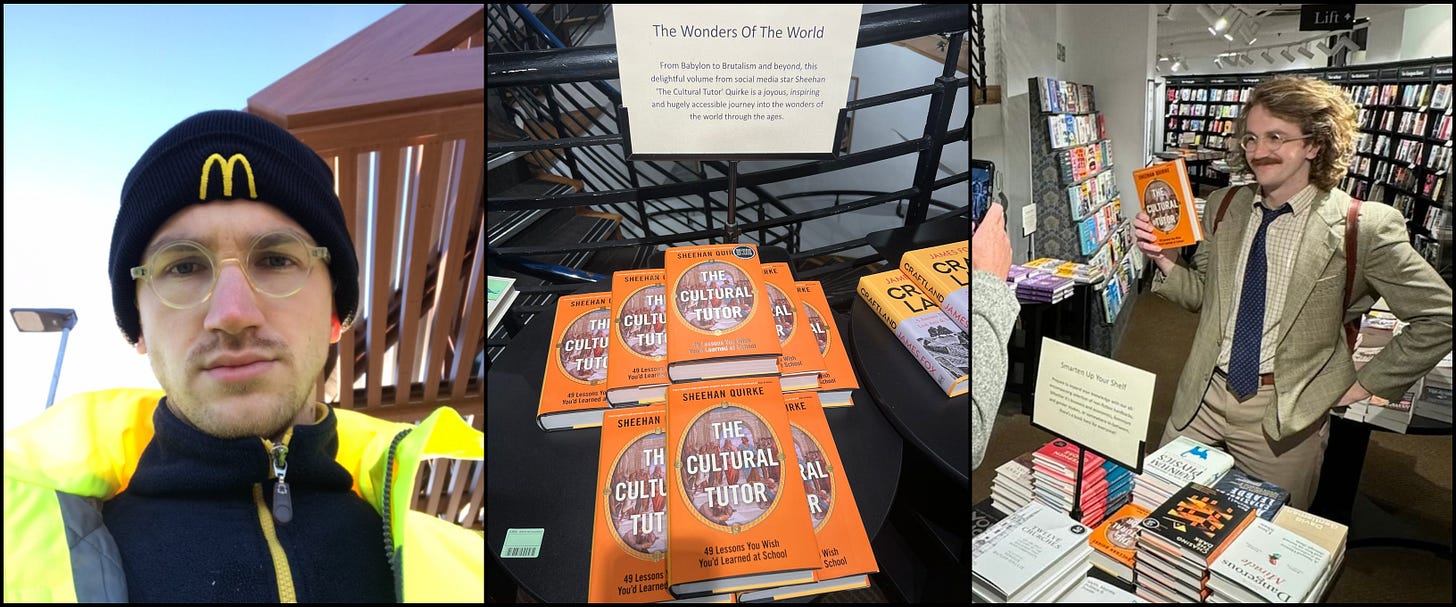

Welcome one and all to the hundred-and-second volume of the Areopagus. It begins with a special announcement: my book, at long last, is out! So you can (to put the matter bluntly) get it here now.

It’s been a peculiar couple of weeks, but on the whole my decision three years ago to quit a job that wasn’t doing me any good, and pursue breathlessly and even slightly recklessly the dream that compelled me above all others, has felt like the right one.

So here we are. For yourself, or perhaps as a gift, for anybody interested in my work already or looking to begin a journey into the rich world of culture — a world so much richer than the one we are led toward by what most conveniently appears in these strange, online times! — there is this book I have written.

(If you happen to order it from Amazon, and think the book worthy of feedback, your reviews on that site are incredibly, incredibly helpful!)

Enough book talk — time rolls on. And the inimitable poet Kabir, writing five hundred years ago or more, kindles our lodestar for this week’s Areopagus:

The light of the sun, the moon,

and the stars shines bright:

The melody of love swells forth,

and the rhythm of love’s detachment beats the time.

Day and night, the chorus of music fills the heavens; and Kabir says,

“My Beloved One gleams like the lightning flash in the sky.”

Illuminated — the seven short lessons begin…

I - Classical Music

Morgenstemning from Peer Gynt Suite No. 1

Edvard Grieg (1888)

Performed by the Berlin Philharmoniker

Saint Francis in the Desert by Giovanni Bellini (1480)

It is quite impossible to know how many times I’ve heard this piece of music, and I suspect it’s similar for you. Morning Mood is one of those classical pieces that has achieved absolute ubiquity, universally recognised even if those who recognise it cannot name it. A hundred films, a thousand TV shows or cartoons, and a million adverts: whenever we are supposed to get the impression of peaceful morning after an uninterrupted night’s sleep, Grieg’s Morning Mood is played — normally followed by a jump-scare or some other form of bathos!

And so the shame is that Morning Mood’s universality has drained its magic; one hears this song usually as a kind of spoof or parody of a bright and beautiful morning, precisely because its association is so concrete in our minds, so overwrought and familiar that playing it sincerely no longer makes sense.

Thus I write about Morning Mood to rescue it from parody; because, when we listen to it properly and manage to cast off those connotations hammered so hard into us… we enter a world of unrelenting musical enchantment.

First, its context: the great Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg initially wrote Morning Mood as incidental music (meaning, background music to the action) for an 1875 production of the play Peer Gynt, written by his compatriot Henrik Ibsen several years earlier. A decade later he took four of its sections and made them into a suite; five years after that he did the same thing with another four sections. Thus there are two Peer Gynt Suites, and Morning Mood is first movement of the first suite.

Unsurprisingly, the scene it originally accompanied was one where the protagonist, the eponymous Peer Gynt, awakens. But, surprisingly, this scene takes place in Morocco — and is introduced with these stage directions and dialogue:

Daybreak. The grove of acacias and palms.

Peer Gynt in his tree with a broken branch in his hand, trying to beat off a swarm of monkeys.

Peer: Confound it! A most disagreeable night.

Not at all what Grieg’s leads us to believe!

Second, the music itself: the opening of Morning Mood is the part we all know, the first fifteen seconds or so, but if we keep listening then the already wonderful music unfolds into something even more moving, swelling, and uplifting. We can somehow hear (even if Ibsen’s actual play would have us imagine otherwise) rays of dawn glittering on treetops and shining softly through the curtains of a window left ajar.

Grieg’s evocation of morning is so compelling and utterly convincing that it exceeds the need for context, and nor should its original and surprising context (of a bad night’s sleep and a morning assault by monkeys) alter that evocation. But, learning its context, I think we can listen to Morning Mood with fresh ears.

Now, it’s impossible not to mention that another of classical music’s most instantly recognisably pieces, In the Hall of the Mountain King, was also composed by Grieg as incidental music to that 1875 production of Peer Gynt, and was the fourth movement of the first Peer Gynt Suite. Many of you will already know this; I, however, had somehow never made the connection! For Grieg to have created two of the most universally recognised songs in the same work is a baffling, brilliant achievement.

Finally: to enjoy the music in a wholly different light, and to find a way of hearing it again for the first time, you can listen to Duke Ellington’s gorgeous jazz arrangement of the Peer Gynt Suite, from 1964. Here’s Morning Mood and, even more unexpectedly, In the Hall of the Mountain King.

II - Historical Figure

The Unknown Pessimist

A few weeks ago one of my good friends told me about something that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about. It’s an ancient Mesopotamian text called The Dialogue of Pessimism, a sort of poem written something like three thousand years ago, although it could be older. It likely originated in the edubba, the formal institution — not so dissimilar from a modern school — for educating and training scribes in Ancient Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq. The edubba had a curriculum which involved, among other things, the reading, memorisation, and writing down of received texts.

That, it seems, was the context wherein the Dialogue of Pessimism either originated or was passed down; texts used for memorisation in the edubba were usually drawn from sources external to the school, whether religious hymns or well-known myths, and so this dialogue may have been included in the curriculum, rather than written for it.

It takes the form of a conversation between a master and his slave. The master explains that he intends to take a particular course of action, and the slave responds with wise words affirming his choice; the master then says he won’t do it, and the slave responds with… wise words affirming his choice. This happens ten times, for ten proposals of increasing magnitude. The second, for example, goes:

M: Slave, listen to me!

S: Here I am, master, here I am.

M: Quickly! Fetch me water for my hands, I want to dine!

S: Dine, master, dine! A good meal relaxes the mind! …the meal of his god. To wash one’s hand passes the time!

M: O well, slave, I will not dine!

S: Do not dine, master, do not dine! To eat only when one is hungry, to drink only when one is thirsty is best for man!

And the sixth:

M: Slave, listen to me!

S: Here I am, master, here I am!

M: I want to lead a revolution!

S: So lead, master, lead! If you do not lead a revolution, where will your clothes come from? And who will enable you to fill your belly?

M: O well, slave, I do not want to lead a revolution!

S: Do not lead, master, do not lead a revolution! The man who leads a revolution is either killed or flayed, Or has his eyes put out, or is arrested and thrown to jail!

Toward the end of the dialogue, the master says he wants to start a business:

M: Slave, listen to me!

S: Here I am, master, here I am!

M: I want to invest silver.

S: Invest, master, invest. The man who invests keeps his capital while his interest is enormous!

M: O well, slave, I do not want to invest silver!

S: Do not invest, master, do not invest! Making loans is as sweet as making love, but getting them back is like having children! They will take away your capital, cursing you without cease. They will make you lose the interest on the capital!

Finally, the master seems to conclude that nothing in life is worthwhile, that all is futile, that any given action can be justified and therefore that nothing is genuinely good or right… and proposes to kill himself:

M: Slave, listen to me!

S: Here I am, master, here I am!

M: What then is good? To have my neck and yours broken, Or to be thrown into the river, is that good?

S: Who is so tall as to ascend to heaven? Who is so broad as to encompass the entire world?

M: O well, slave, I will kill you and send you first!

S: Yes, but my master would certainly not survive me for three days!

The slave’s response is magnificent, and just as majestically witty now as it must have been three or four thousand years ago, simultaneously giving us a neat ending to this narrative and also throwing open its interpretative doors.

What to make of this text? Its title — Dialogue of Pessimism — was only suggested in the 1920s, and is, if not misleading, at least biased, and presents us with a specific interpretation that isn’t necessarily correct. Is it actually pessimistic, or is it mocking pessimism? It does seem satirical, but may have been intended as purely comic, from the time-honoured genre of foolish (or, more charitably, eccentric) master and witty servant, in the mould of Jeeves and Wooster or Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

Alternatively, it may have been a thoroughly serious dissection of the uselessness and capriciousness of old proverbs (which is what the slave seems to speak in) and therefore an argument in favour of more considered, logical reasoning for the actions we take. Or, of course, it may be a genuinely existential text, one that surveys the futility and meaninglessness of life and stands as a precursor not only to Ecclesiastes but also to Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Camus, or any other writer usually thrown into that category — and, in some ways, represents a more concise and superior statement of all they ever had to say!

But I don’t think we need to find an answer right now. Most important, most obvious, regardless of its original purpose, is that the Dialogue of Pessimism explores — regardless of which ‘side’ it takes — a set of feelings and thought processes familiar to all of us. Who hasn’t considered doing something and found perfectly adequate reasons both for doing and not doing it, only to fall back upon ceaseless indecision? Who hasn’t worried that their opinion changes based on the most recent thing or person they listened to? Who hasn’t sensed a whole world of possibilities out there, only to retreat inward and avail themselves of none?

We don’t know the name of the person who wrote this — was it a poet? a priest? a young scribe? a king? a servant? — and, save for new evidence, never will. But, whoever that person was and however they were called, I thank them for their work! We live in an age when things like procrastination and doubt, decision paralysis and loss of purpose, seem worse than ever. Moreover, their prevalence seems tied to the Internet and its overwhelmingness, drowning us every day in an endless river of content and shattering our attention spans thereby. But, long before computers or video games or flushing toilets or Hollywood or LinkedIn, we find an utterly flawless and all-encompassing evocation of those apparently ‘modern’ feelings.

This Mesopotamian poet has, unwittingly, given us consolation against the anxieties of twenty-first century life. The Dialogue of Pessimism reminds us that these problems are not new, that the Internet has not necessarily trapped us in an existentialist loop, and that the challenges we conceive of as uniquely ours have been at least struggled with, and perhaps even overcome, by our ancestors.

No ancient Babylonian could have foreseen the technologies and political systems by which we now live. But, could we teach that poet our language and give them our books to read and podcasts to browse, the problems we’re obsessing over would be thoroughly familiar to them. And so the Dialogue of Pessimism is also testament to the permanent power of literature. Scientific theories are challenged and disproven; technologies become obsolete; political ideologies shift in response to wider context; literature, if truthful, is eternal.

(The friend who told me about this was called Matt; it is only the latest of countless curious and fabulous things he’s recommended. And Matt has a YouTube channel, by the way. He doesn’t know I’ve written this, so a surprise bump in subscribers (should you choose to so subscribe!) will be a nice surprise for him.)

III - Art

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb

Hubert and Jan van Eyck (1432)

Analyses of the Ghent Altarpiece, otherwise called The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, usually focus on one of two things. Either its wild history of repeated theft, dismemberment, reunion, and restoration, or breaking down each of its panels and their extensive details and symbolism. You can see why. It is an epic, a total recreation in visual art of Biblical scripture, a complete vision of Catholic faith in one, vast polyptych — it is, I dare say, something like the Sistine Chapel of Northern Europe.

But I want to talk about the bit that gets less attention: the front. Because this altarpiece is (like many) folding — and can be closed. People usually talk about the interior panels, but I think the exterior panels are more revealing, and help us understand the interior better.

The Ghent Altarpiece was made by the van Eyck brothers, Hubert and Jan (of Arnolfini Portrait fame), from sometimes in the mid-1420s through to 1432. It was commissioned by Lysbette Borluut and her husband, Joos Vijd, the vice-burgomaster of Ghent, who was otherwise a merchant and churchwarden of St Bavo’s Cathedral, where the altarpiece was installed. You can see them on the front panels, painted life-size and with quite astonishing, photorealistic precision:

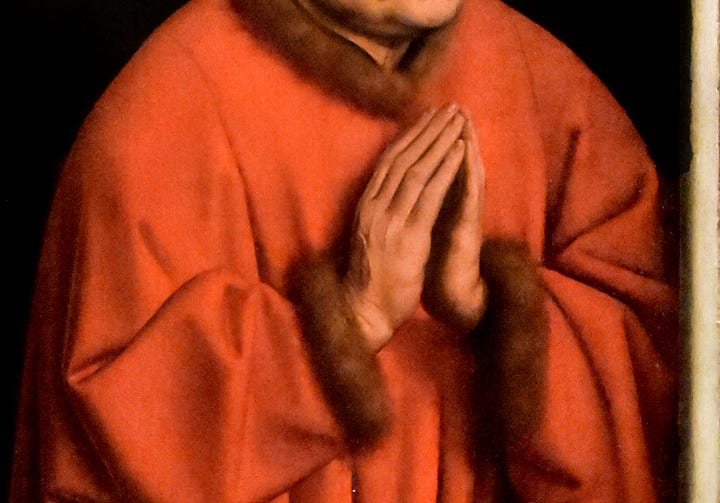

This scrupulous attention to detail, in particular to materials and their textures, painted with the full illusion of three-dimensional depth, are central characteristics of Early Netherlandish Art, otherwise called Flemish Primitivism. Notice, for example, the marble hand of the statue of John the Baptist, and the faint glistening of its fingers:

Remember, the van Eycks painted this before Leonardo da Vinci was even born! And there is, throughout, a virtuoso freedom to the Ghent Altarpiece. Oil painting, only recently introduced to the Netherlands, and which allowed for far greater precision and vividity than was possible with previous methods, had already been mastered and taken to its extreme by the van Eycks. Notice, for example, that the real frame holding the panels has been made to cast a shadow into the painting:

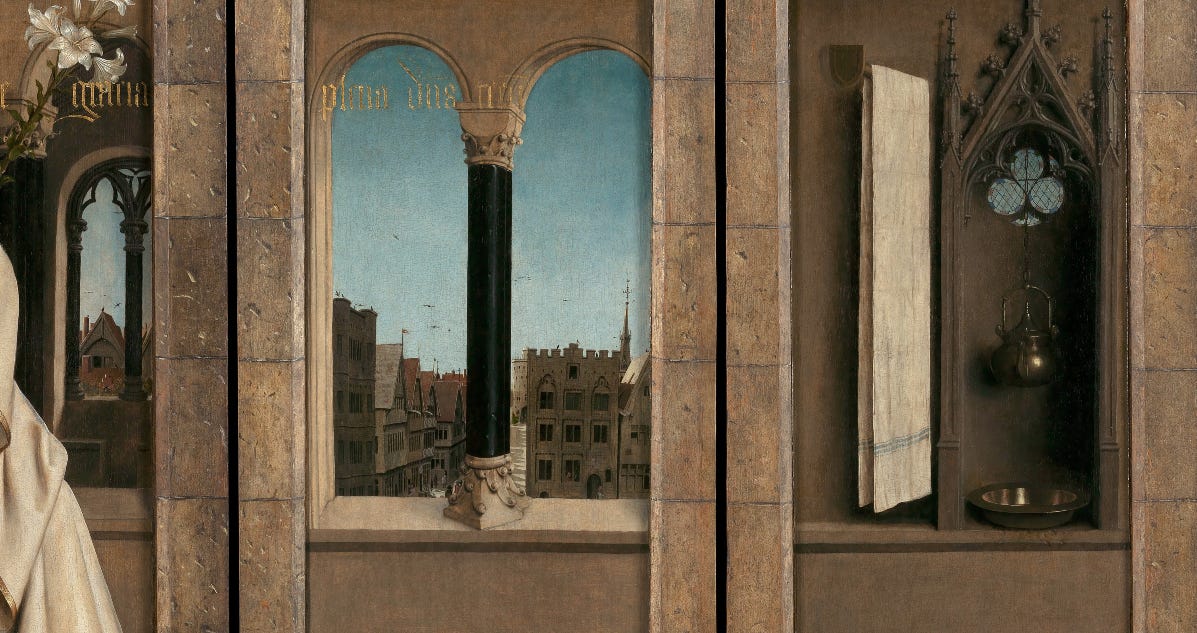

Another key element of Netherlandish Art was — particularly compared with Italian art — its domesticity; the scene of the Annunciation (when the Angel Gabriel informs Mary that she will bear Christ) takes place in a contemporary Flemish household, with a view of what seems to be Ghent, and its steep gables and canals, behind:

Other than the painting in itself, as a supreme example of Netherlandish Art, the Mystic Lamb is a window into Late Medieval life, into the difference between how we and our ancestors thought about and experienced “art”. See, the Ghent Altarpiece is where it was always supposed to be in: in a church, a place of worship, where it could be (in some sense of the word) used by the community. And, crucially, the altarpiece was only opened on special occasions, on certain feast days or celebrations.

That is why we should focus our attention on the front, rather than interior, panels — because those are the ones people throughout history have seen most often! And notice the difference between what is usually seen and what is unusually seen. The exterior has muted colours, with the two patrons set against black backgrounds and the statues in greyscale, while even the sybils and prophets in the lunettes are set in plain, stone cells, and the scene of the Annunciation is played out (as we said) in an austere, contemporary Flemish house.

All of that contrasts with — to be seen, surely, with delight and awe — the interior: shimmering green fields, iridescent blue skies, the angels in their robes and with their sparkling instruments, the knights in their glittering armour and all their colourful pageantry, and the unremitting luxury, grandeur, and splendour of the central figures:

But this is something that we, in the twenty first century, necessarily struggle to appreciate in its fulness; we can notice the difference… but can we feel it? The paintings I’m showing you now, broadcasting their digital facsimiles around the world, to be viewed on a thousand different phones or laptops, in innumerable situations and places, could once upon a time have been seen but in one particular place, in one particular setting, and only on certain special dates.

Such an observation is hardly original, of course. But I don’t believe the gulf is quite so wide as some have suggested! Because, although the precise experience of seeing an unfolded altarpiece on rare occasions isn’t really available us, the broad lines of such an experience are. Many of us have films that we only watch at certain times of the year, whether on personal anniversaries or at times like Christmas. I, for one, have a small catalogue of films and poems I watch and read only on Armistice Day, on the 11th November, relating to the First World War. Similarly, there are certain songs we make sure to avoid hearing except for at particular times, or with particular people.

Such efforts represent our attempts to recreate, even in the modern and digitised world, the same specialness that came with seeing the interior of the Mystic Lamb for the people of Ghent all those centuries ago. And, bearing that familiar habit in mind, I think the Mystic Lamb — having read or not read analyses of its multitudinous meanings and symbols — begins, not to “make” more sense, but (if I can rely on some enallage here) to feel more sense.

IV - Architecture

Sterner’s House

Domestique Nouvelle?

When we talk about architecture it’s only natural that we focus on the biggest and grandest of buildings, on monuments and colossi: Hagia Sofia, Chrysler Building, Parthenon, Rani ki Vav, or Chichen Itza. These buildings, beyond being iconic in themselves, also tend to embody the principles and motifs of the broader architectural styles they represent. They are, simply, unavoidable.

But you cannot make a city of monuments; the majority of buildings in any given human settlement, and the vast majority of buildings we’ve put up since the dawn of civilisation, have been homes. And this building, designed by the architect Ernest Delune for the glassmaker Clas Sterner, is precisely that: a house. It was completed in 1902, at the height of Art Nouveau, in the city where (at least in its continental form) the movement first arose: Brussels.

House. It’s a word that doesn’t inspire the same feelings of awe as palace, castle, or temple; but it is, ultimately, a more important word, and Delune shows what is possible for the humble house when we apply our full imagination to it.

What joy a front door can bring! Little wonder images of this door have gone viral online so many times; but the real wonder is that its charm (a better word than beauty, I think!) rests in the loving use of simple materials, not in the extravagant use of expensive ones.

So Sterner’s House is a wonderful example of Domestic Architecture; in particular, of Domestic Art Nouveau. From this building alone you can deduce the design principles that governed Art Nouveau in general: asymmetry, flowing lines (even on the door’s hinges!), a certain ‘bulbousness’ (note the two round windows), a focus on craftsmanship (stained glass), an embrace of modernity (the floor-to-ceiling, trapezoid bay window), and attention to detail (the vertical letterbox, the stylised number six):

You can also see that Art Nouveau was a regeneration and reinvention, rather than a rejection, of historical or traditional design. Between the 19th century Revivalists, who cleaved too closely and conventionally to the past, and the 20th century Modernists, who consciously cast it off, there shone the beautiful, brief mid-point of Art Nouveau, teetering on the brink between two eras and thus, inevitably, bursting with life. And, a century later, even their humblest buildings — houses, no less! — still bring us pure and interminable delight. Much we might learn, I dare say, from the days of Art Nouveau, as we go about building our twenty-first century houses.

V - Rhetoric

Democritus versus Heraclitus

There’s an ancient question that asks: “are you like Democritus or Heraclitus?” Michel de Montaigne, writing in the 16th century, explains it for us:

Democritus and Heraclitus were two philosophers, of whom the first, finding human condition ridiculous and vain, never appeared abroad but with a jeering and laughing countenance; whereas Heraclitus commiserating that same condition of ours, appeared always with a sorrowful look, and tears in his eyes:

Voltaire put his own spin on it, saying:

Life is a comedy to those who think; a tragedy to those who feel.

Well, who of the two are you? It’s a compelling dichotomy, one that seems to ring true and forces you to re-evaluate your own perspective on this world of ours and on our fellow creatures, perhaps even forcing you to interrogate beliefs you’ve always held unquestioningly, and therefore to struggle with what seemed like the sure foundations of your worldview.

But, of course, it’s a trick.

Ivan Turgenev did the same thing, stating that all human beings are fundamentally either Quixotic — i.e. Don Quixote, of Miguel de Cervantes’ eponymous novel — or Hamletian — i.e. Hamlet, of Shakespeare’s play. Or there’s the French scholar Raymond Queneau, saying:

One can easily classify all works of fiction either as descendants of the Iliad or of the Odyssey.

These are false dichotomies, meaning that they present two mutually exclusive choices — a dichotomy — as the only ones available to us, and force us to pick one without revealing that there are, in fact, other possibilities — which is where the falseness comes in.

Worst of all about these false dichotomies is that they kind of work. Forced to choose, you can decide whether you are more like Democritus or Heraclitus, more like Hamlet or Don Quixote, and whether a particular book takes after the Iliad or Odyssey. But I could just as soon say, “There are only two kinds of football fan: those who prefer Barcelona, and those who prefer Real Madrid”. If you know something about football — and the differences between those clubs — this makes ostensible sense. Only, of course, I invented it on the spot, without real thought, and in the end it’s a notion that simply serves to sow needless division.

But false dichotomies work because of what they obscure, and by forcing us, invisibly, into accepting their premises. Presenting listeners or readers with a false dichotomy is one of the oldest entries into the rhetorical ploybook, and advertising gurus and politicians continue to use it today, almost always to very great effect. Even film-makers! When Harvey Dent says, in The Dark Knight:

You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become a villain.

That’s a false dichotomy! There are other possibilities, but this choice is presented so alluringly that we are inclined to believe Mr Dent. And the trouble, you can sense, is that alternative, real avenues of choice are closed to us by the rhetorical wizardry of those we listen to, and false dichotomies may thus corrupt how we actually behave.

I needn’t listen examples of political false dichotomies; listen to any speech and you’ll hear a dozen. But it isn’t only politics. Pay attention to adverts and you’ll notice that, ever so slyly, they very often present you a choice (between the product they’re selling and all the others out there) with the goal of pressuring you into accepting a false premise and concluding that their product is the best option.

All of which is to say, you needn’t pick between Democritus and Heraclitus. There are other options, and you can be one or the other from time to time. But this talk of false dichotomies is, above all, further proof of why studying rhetoric is so important, and now more than ever. Because rhetoric isn’t just about learning to speak better; it is also (and perhaps even primarily!) about learning to listen better, about learning to detect the tricks being played on us by all who stand to benefit from doing so.

VI - Writing

Be Stubborn

There is a bit of writing advice (and life advice in general) that we hear repeated again and again, along the lines of, “Be yourself,” or “Trust yourself”, and so on. There is a hard core of truth to this suggestion, but it’s been said so often and so mechanically that the lustre of its truthfulness has worn off and the idea has turned into a trope. Worse, it’s become a trope easily discredited or flipped on its head in some sort of Wildean way, as when T.S. Eliot said:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

Eliot was correct, but all he’s done is explain (in a witty and memorable way) the nature of influence. What he said doesn’t remotely negate the idea that we should, also, and above all, be true to ourselves. So how to rescue this cliché from clichédom? The gargantuan mind of the gargantuan artist Victor Hugo will do it for us.

He wrote a three hundred page essay (i.e. a book) in 1864, called Shakespeare. The title is (as Hugo says in the prologue) misleading; really it is an essay about artistry and genius in general. Consider this a reading recommendation; Hugo’s essay is broad in scope and, like his prose, thoroughly entertaining and utterly convincing in his own, highly Romantic, bulldozer-like way. It’s a kind of wild and virtuoso kaleidoscopic of hilariously sweeping epigrams, such as:

The more we advance North, it seems as if the increased thickness of the fog increases the greatness of the poet.

Or:

For him who has had no other action but that of the mind, the tomb is the elimination of the obstacle. To be dead, is to be all-powerful.

Or:

You ask in what poets can be useful? In imbuing civilization with light — only that.

In any case, and returning to the point of this section; consider this paragraph, from the fifth chapter of a section called Criticism:

Imitation is always barren and bad.

As for Shakespeare… he is, in the highest degree, a genius human and general; but like every true genius, he is at the same time an idiosyncratic and personal mind. Axiom: the poet starts from his own inner self to come to us. It is that which makes the poet inimitable.

Examine Shakespeare, dive into him, and see how determined he is to be himself. Do not expect any concession from him. It is not egotism, but it is stubbornness. He wills it. He gives to art his orders,—of course in the limits of his work; for neither the art of Æschylus, nor the art of Aristophanes, nor the art of Plautus, nor the art of Macchiavelli, nor the art of Calderon, nor the art of Molière, nor the art of Beaumarchais, nor any of the forms of art, deriving life each of them from the special life of a genius, would obey the orders given by Shakespeare. Art, thus understood, is vast equality and profound liberty; the region of the equals is also the region of the free.

…

Let men of genius remain in peace in their originality… Each of them is in his cavern, alone. They hear one another from afar, but never copy one another. We are not aware that the hippopotamus imitates the roar of the elephant, neither do lions imitate one another.

Diderot does not recast Bayle; Beaumarchais does not copy Plautus, and has no need of Davus to create Figaro. Piranesi is not inspired by Dædalus. Isaiah does not begin Moses over again.

…

Shakespeare’s work is absolute, sovereign, imperious, eminently solitary, unneighbourly, sublime in radiance, absurd in reflection, and must remain without a copy.

Hugo is giving breadth and depth, in his own weird manner, to the statement with which we started, the old cliché: “Be Yourself”. Written and proclaimed like this — something like: Stay in your cavern, Be unneighbourly, Be stubborn, Be eminently solitary — the advice regains its truthful lustre. In which case, thusly renewed, the next time you set out to write something (however small) bear in mind Hugo’s eccentric but faithful recasting of that one little urge gnawing away inside all of us, and… be stubborn!

VII - The Seventh Plinth

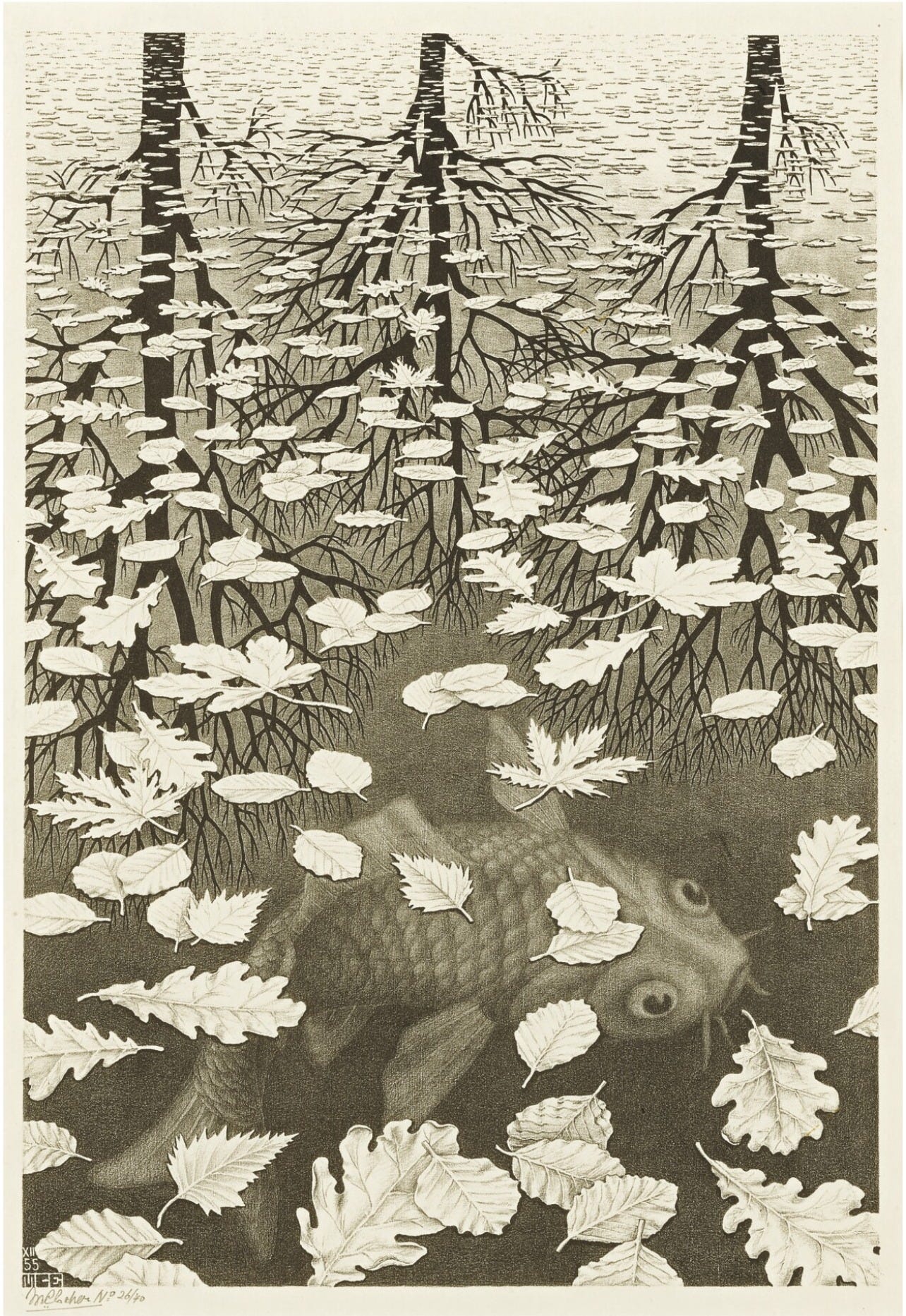

Reflections

You expect to wake up, on the morning of being a published author, and find that life is different. This is true, from a certain point of view, and I do hope the book will lead to exciting and wonderful places! But it is, in another and more profound way, not quite the case. Because the question I’ve been asking myself of late isn’t where this book will take me or how it’s been received; the only question has been, “do I like it?”

I suppose, in an altered sense, all I’m doing is echoing what Hugo said. Because, in the end, nothing matters except for the work itself, whatever that work is — a book, an essay, a table, a tour, a spreadsheet, a match, a meeting, or anything at all we do from day to day or year to year — regardless of surrounding context, of relative and impermanent phenomena; all the rest is ripples on water, soon to be quelled, and our work is the pebble, plunging through its surface and descending to the most real and eternal depths!

Question of the Week

The most recent question of the week, rolled over because of book-related newsletters, was me asking you to ask me a question. I’ll get round to answering them, I promise! But, for now, as we settle into Autumn and these post-launch days (when my energies can wholly resettle on this beloved Areopagus) I think it worth returning to the familiar formula.

So, for this week’s question, inspired by Sterner’s Studio:

If you could choose any architect to design your home, living or dead, who would it be?

Email me your answers and I’ll share them in the next Areopagus.

And that’s all

It seems to me that, of so much missing in this modern world of ours — in a modern life lived by its ordinariest and convenientest course — poetry stands out as something we most gravely lack. It runs contrary to the kind of neatly-packaged, commercially-calibrated, customer-focussed, AI-sloppy, clickbaity, convenient nature of all those things we are led to “consume” by the Internet and by our consumerist culture in general, and lets us access other parts of our own spirits and hearts and minds which are always there, have not and can never go away, but which are dimmed by the one, and uplifted by the other.

That is, more or less (or, really, for the simple love of it), why I like to begin (sometimes) and end (always) the Areopagus with poetry. Today is no different, and for my closing words I turn again to the mystical, truth-seeking, orthodoxy-rejecting 15th century saint-poet Kabir, translated by Rabindranath Tagore:

The jewel is lost in the mud,

and all are seeking for it.

Some look for it in the east, and some in the west;

some in the water and some amongst stones.

But the servant Kabir has appraised it at its true value,

and has wrapped it with care in the end

of the mantle of his heart.

Farewell!

Yours,

The Cultural Tutor

The Dialogue of Pessimism is a wonderful anticipation of AI LLM.

Ordered. Looking forward to reading it, from an ex-Maccies crew member. After all this free insight I felt it's the least I owed you.