Welcome one and all to the hundredth volume of the Areopagus. It seems only right, by a strange cosmic fate-twist, that the most wondrous occasion of this hundredth volume is also marked by the recent arrival of the first physical copies of my new book. Not unhandsome, I think!

Well, this marks the culmination of a lifelong dream that started at least 23 years ago. But more on that later. For now, I have only two things to say. First, that any and all links to pre-order the book (for international deliveries you can go to Blackwell’s) are to be found here. Second, that a great muchness of my gratitude goes to you, my Dear Readers. When I started the Areopagus three years ago I had no book, nor any book deal, to speak of — only a dream, a conviction, and a laptop. That I can now hold a book in my hands and say that I wrote it is not only due to those three things; it is also, perhaps even primarily, due to a fourth thing I did not have when I started out: readers.

Thank you.

And now — back to the show…

I - Classical Music

8 Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, No. 1 in C

Antonín Dvořák (1878)

Performed by the Wiener Philharmoniker

The Printing of the Bible of Kralice in Ivančice (from The Slav Epic) by Alphonse Mucha (1914)

We begin, this week, where the Areopagus began three years ago: with Antonín Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, specifically the first (of sixteen in total). I choose it now, and chose it then, because it is one of the most purely joyous, most unashamedly celebratory pieces of music ever written.

These Slavonic Dances were made in two batches. The first eight were written in 1878, on the advice of fellow composer Johannes Brahms and at the specific request of a publisher. They were immensely successful and established Dvořák’s international reputation. In 1886 he returned to the Slavonic Dances — again, at the request of his publisher — and wrote another eight, which once again proved to be critical and commercial successes.

Their initial inspiration was Johannes Brahms’ own Hungarian Dances, which had — in keeping with a growing trend involving the likes of Liszt and Chopin — been influenced by the folk music of Central and Eastern Europe. This trend was, in part, purely musical; folk music enthused the Age of Romanticism with a new vigour and texture. But it was also quasi-political. Drawing on folk music was a crucial part of nation building, of giving nation states (which are normal now, but were not normal in the 19th century!) a coherent identity. Dvořák’s role in this process, and the role of many other artists (like the great Czech painter Alphonse Mucha, whose work is included above) cannot be understated.

Composers studying, rooting through, and adapting folk music was the 19th century classical equivalent of modern musicians seeking sounds from beyond the scope of popular music, searching for something new in the underground trends of the day. And, of course, Dvořák being urged by his publisher to produce music that would be a guaranteed commercial success is something else we recognise in the present.

The Slavonic Dances were also written, at first, for piano rather than orchestra. Specifically, for two players. Thus the sheet music was primed for joint performance at parties, and quickly sold out. One can easily imagine the excitement in 1886 when Dvořák’s latest round of Slavonic Dances were released, not so different from our rush (once to the record store, now to YouTube or Spotify) when an artist returns to the sound and style of their greatest hits. As Telemachus says to his mother in the Odyssey:

…for men praise that song the most which comes the newest to their ears.

We always want to hear the newest of songs; it was true in Ancient Greece, it was true in the 19th century, and it’s true in 2025.

II - Historical Figure

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

I have quoted her poetry often enough, and so it is only right that I finally write about her more fully: Elizabeth Barrett Browning, known before her marriage as Elizabeth Barrett Barrett, or simply as EBB.

She was born in 1806, the eldest of twelve children, to a wealthy middle class family. Her childhood was more or less idyllic, spent at a large manor in Worcestershire, near the Malvern Hills, called (not inappropriately, given her career and the themes of her poetry) Hope End. The young Elizabeth taught herself Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and Hebrew — so she could read great works of literature in their original tongue — and wrote her first epic, The Battle of Marathon, at just fourteen years old.

No doubt Barrett Browning could not have done this but for the time and means afforded by her family. Still, being provided with such privilege does not necessarily mean that people will capitalise on their advantages; she flung herself, with full endeavour, through the door of opportunity that good fortune had opened for her.

At fifteen Barrett Browning fell sick, and would remain sickly — her sufferings eased by the poisoned chalice of laudanum — for the rest of her life. The family moved between Devon and London for the next few years, until they finally settled in London in 1838. Her mother had died ten years earlier and her brother had died, drowning off the Devon coast, in 1836. And so in London, feeling trapped in the bedroom of her overprotective father’s house, with her brother’s death and her own ill health weighing heavily on her, Barrett Browning wrote the collection that would establish her national reputation: a volume published in 1844, simply called Poems. These six lines, from a poem called Cheerfulness Taught by Reason, seem to represent the heart of these early works:

O pusillanimous Heart, be comforted

And, like a cheerful traveller, take the road

Singing beside the hedge. What if the bread

Be bitter in thine inn, and thou unshod

To meet the flints ? At least it may be said

‘Because the way is short, I thank thee, God.’

Her star continued to rise thereafter. And with the publication of Aurora Leigh in 1857, a verse novel about the life of a young woman, ‘EBB’ cemented her status as one of the Victorian Era’s leading poets — and most brilliant spirits.

See, Barrett Browning had a fearless moral conscience: she wrote openly and frankly about women’s rights, slavery, the treatment of poor children, and of all the evils that plagued the 19th century. Obvious to us now; less obvious, or less easily criticised, at the time — like the evils of all ages. Her opposition to slavery caused tensions with her father, whose business relied on it; this did not deter Elizabeth. She had a large American audience (including Emily Dickinson!) and continued to write openly on the necessity of abolition. Barrett Browning was horrified by the fact that her own comfortable life had been possible only because of slavery, and was convinced that working to abolish it amounted to the very least she could do.

What of Aurora Leigh? Rather than giving you three dozen quotes, or talking over it too much, I think it best to offer just one, extended quote:

The critics say that epics have died out

With Agamemnon and the goat-nursed gods—

I’ll not believe it. I could never dream

As Payne Knight did, (the mythic mountaineer

Who travelled higher than he was born to live,

And showed sometimes the goitre in his throat

Discoursing of an image seen through fog,)

That Homer’s heroes measured twelve feet high.

They were but men!—his Helen’s hair turned grey

Like any plain Miss Smith’s, who wears a front;

And Hector’s infant blubbered at a plume

As yours last Friday at a turkey-cock.

All men are possible heroes: every age,

Heroic in proportions, double-faced,

Looks backward and before, expects a morn

And claims an epos.Ay, but every age

Appears to souls who live in it, (ask Carlyle)

Most unheroic. Ours, for instance, ours!

The thinkers scout it, and the poets abound

Who scorn to touch it with a finger-tip:

A pewter age,—mixed metal, silver-washed;

An age of scum, spooned off the richer past;

An age of patches for old gaberdines;

An age of mere transition, meaning nought,

Except that what succeeds must shame it quite,

If God please. That’s wrong thinking, to my mind,

And wrong thoughts make poor poems.Every age,

Through being beheld too close, is ill-discerned

By those who have not lived past it.

This is, in part, a direct reference and rebuttal to Thomas Carlyle’s monumental On Heroes, a wildly influential work that I have quoted before. There’s nothing else like it. And yet, despite Carlyle’s altogether apocalyptic magnificence as a writer and thinker, Barrett Browning totally pulls the rug out from under his earth-shattering jeremiad with flowing, uncomplicated prosody and honest, unassuming observations. Her understated, wholly reasonable poetry makes Carlyle (and others like him) seem rather melodramatic and ridiculous by comparison.

What saves her poetry from being merely sentimental is her objectivity and her frankness; she is not prone to idealising, only to hoping, and hoping without shame. I do think there is something of Barrett Browning’s sober, indefatigable, wholly unnaive optimism that the world seems to lack these days.

Now, it would be improper to write about Elizabeth Barrett Browning without mentioning her husband, Robert Browning (and vice versa, we must say!) — because theirs was one of the greatest, most moving romances of the 19th century. He was a brilliant but struggling poet six years her junior, who had fallen in love with her poetry and wrote to her in January of 1845 (the two having never met!) to express his admiration, beginning:

I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett,—and this is no off-hand complimentary letter that I shall write,—whatever else, no prompt matter-of-course recognition of your genius, and there a graceful and natural end of the thing.

To which Elizabeth responded:

I thank you, dear Mr. Browning, from the bottom of my heart. You meant to give me pleasure by your letter—and even if the object had not been answered, I ought still to thank you. But it is thoroughly answered. Such a letter from such a hand! Sympathy is dear—very dear to me: but the sympathy of a poet, and of such a poet, is the quintessence of sympathy to me! Will you take back my gratitude for it?—agreeing, too, that of all the commerce done in the world, from Tyre to Carthage, the exchange of sympathy for gratitude is the most princely thing!

Thereafter they struck up a correspondence that would last nineteen months, including precisely ninety-one meetings in person. Their letters to one another are tender and touching in the highest degree, and tell a complete love story of two remarkable minds and even more remarkable spirits, revealed through a mixture of straightforward language and quite delightfully poetic wit and modesty, ranging from the theology of love to casual gossip about friends. I would gladly dedicate this whole Areopagus to excerpts from their letters — but cannot. A couple must suffice. Such as Elizabeth writing in December 1845:

Now, 'ought' you to be 'sorry you sent that letter,' which made, and makes me so happy—so happy—can you bring yourself to turn round and tell one you have so blessed with your bounty that there was a mistake, and you meant only half that largess? If you are not sensible that you do make me most happy by such letters, and do not warm in the reflection of your own rays, then I do give up indeed the last chance of procuring you happiness. My own 'ought,' which you object to, shall be withdrawn—being only a pure bit of selfishness; I felt, in missing the letter of yours, next day, that I might have drawn it down by one of mine,—if I had begged never so gently, the gold would have fallen—there was my omitted duty to myself which you properly blame. I should stand silently and wait and be sure of the ever-remembering goodness.

And Robert responding:

But did I dispute? Surely not. Surely I believe in you and in 'mysteries.' Surely I prefer the no-reason to ever so much rationalism ... (rationalism and infidelity go together they say!). All which I may do, and be afraid sometimes notwithstanding, and when you overpraise me (not overlove) I must be frightened as I told you.

It is with me as with the theologians. I believe in you and can be happy and safe so; but when my 'personal merits' come into question in any way, even the least, ... why then the position grows untenable: it is no more 'of grace.'

Do I tease you as I tease myself sometimes? But do not wrong me in turn! Do not keep repeating that 'after long years' I shall know you—know you!—as if I did not without the years. If you are forced to refer me to those long ears, I must deserve the thistles besides. The thistles are the corollary.

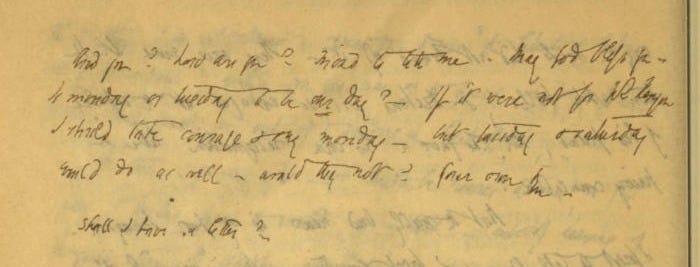

One wonders whether our modern texts and messages will have the same weight in two hundred years’ time. Though, of course, much of their writing to one another is wonderfully familiar, as when Elizabeth ended one letter:

And you? how are you? Mind to tell me. May God bless you. Is Monday or Tuesday to be our day? If it were not for Mr. Kenyon I should take courage and say Monday—but Tuesday and Saturday would do as well—would they not?

It was during their courtship that Barrett Browning wrote her Sonnets from the Portuguese (an intentionally misleading title; they have nothing to do with Portugal). They were published in 1850 — as ever, to great success and acclaim. Her love poetry is, perhaps, her finest work; romantic but not generic, hopeful but not idealised, realistic but not bland, and truthful but not reductive. The most famous is number XVIII, beginning:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

The rest are worth reading in full; they rank with the greatest love poetry ever composed. Consider, from XVII:

I seek no copy now of life’s first half:

Leave here the pages with long musing curled,

And write me new my future’s epigraph,

New angel mine, unhoped for in the world!

This all culminated in September 1846, when Robert proposed. This was rejected — not by Elizabeth, but by her father, and repeatedly. So they married in secret and a week later eloped to Italy, where they spent the rest of their married life. Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence in June 1861, leaving behind her husband Robert, their son Penn, and a poetic legacy that has surely made the world a better and more love-filled place. Her final word was, simply:

Beautiful.

Theirs was the true union of two souls. In a modern world where ‘dating’ and ‘romance’ and ‘love’ are under more scrutiny than ever, the example set by the Brownings is one we stand to benefit from learning about and, perhaps, even emulating. You can read their letters online, in two volumes, here and here. So we end with this extraordinary sculpture by Harriet Hosmer, who met the Brownings in Rome, and made a cast of their clasped hands, united forever both in verse and bronze:

III - Art

Still Life with Herring

Suzanne Valadon (1936)

There’s something about this painting (and the work of Suzanne Valadon more generally) that I struggle to describe. See, I cannot confess to being the world’s biggest fan of still lifes. They are occasionally interesting, but rarely arresting. Not so with Valadon, who was able to paint the most ordinary things — bouquets of flowers, fish on a plate, tablecloths, chairs — with a kind of vividity that stops short whatever train of thought I’m pursuing and leaves me spellbound. She is unsentimental, but not cold; expressive, but not overwhelming.

You might call it a ‘storybook’ quality. In fact, Valadon’s work reminds me of the Mr. Men books that I so enjoyed as a child. This comparison with childrens’ books isn’t to denigrate Valadon’s style; it’s a kind of praise! You can tell when an artist has found a pure, honest, authentic style when their art doesn’t age. Valadon’s work — like that of all the best painters — is just as vigorous now, just as fresh, as it must have been over one hundred years ago. Above all I would say she brings out the loveliness or curiousness of things in and of themselves, regardless of what exactly they mean, and without trying to convince us too intrusively of what she thinks they mean or show us too tendentiously what she feels about them. This is why I call it a childlike, ‘storybook’ quality — childlike, but not childish. When we are children we look at things with fresh eyes and open hearts, unimpeded by connotations or expectations. Such is Valadon’s work, and it’s something she also brings to her landscapes, like these of Landscape at Saint-Bernard (1932) and Le Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre (1917):

And her portraits, as of Madame Lévy (1922) and Young Girl in Front of a Window (1930):

To take a more technical turn, Valadon is a perfect example of Post-Impressionism. This movement, as its name suggests, was a successor to and development of Impressionism, which had emerged in the 1870s. It is an extremely broad term which covers an awful lot of ground. So the best way to think of Post-Impressionism is as a bridge between Impressionism, which ultimately remained faithful to how the world looks, and those increasingly experimental art movements like Expressionism or Cubism, which were less about how the world looks and more about how it feels.

Thus there’s a kind of tension with Post-Impressionism, a sense that paintings are being pulled in two directions at once. Notice, for example, in all her paintings included here, how Valadon gives everything a clear black outline. This is, of course, not how the world actually looks. And yet Valadon does not dispense with the genuine colours of reality (as somebody like Edvard Munch or Picasso did!) and sticks to the greens, blues, and browns that she actually saw. This tension is where the magic and liveliness of Post-Impressionism, and of Valadon, emerges.

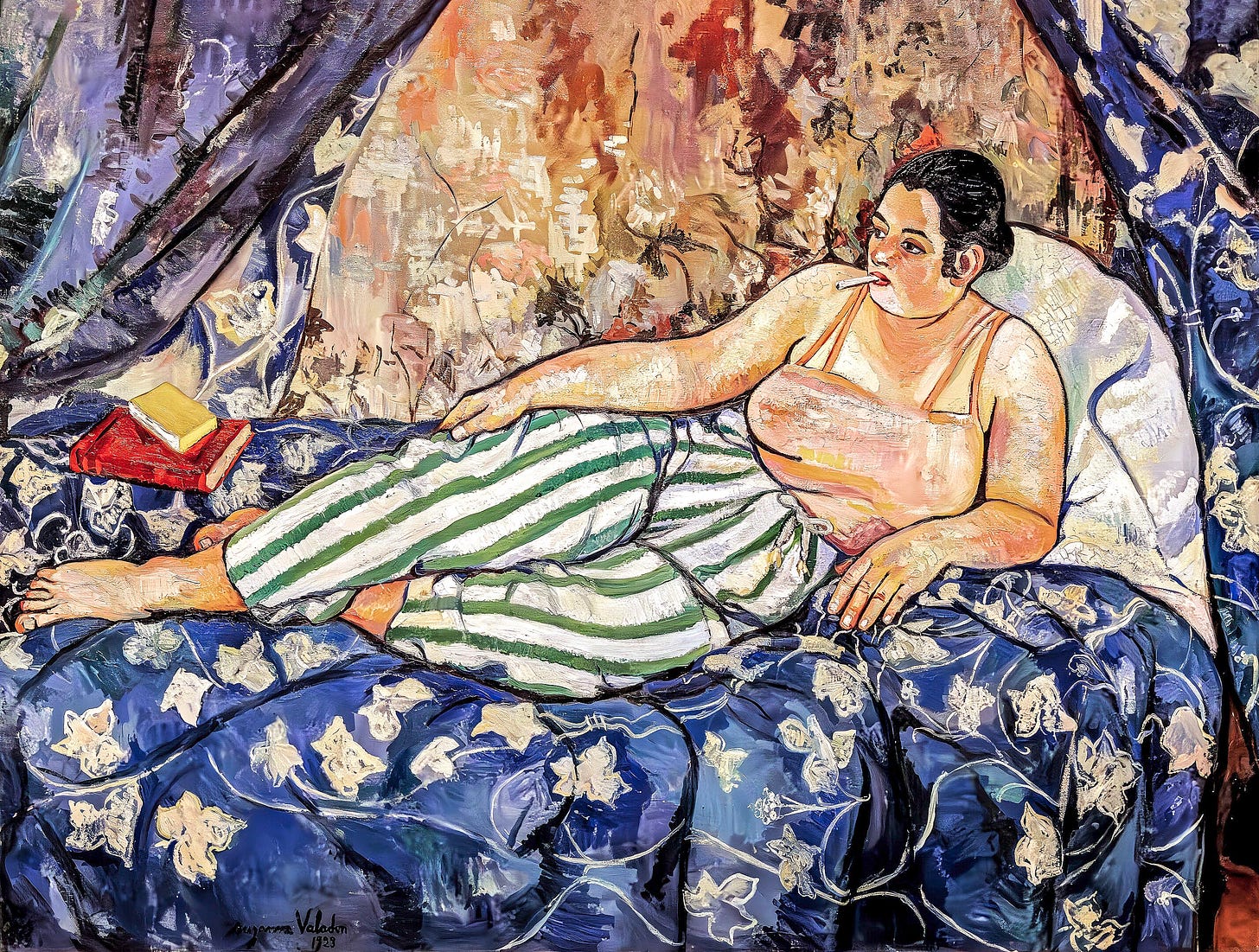

Valadon herself was an extraordinary character, and quite fearless. In her most famous painting, The Blue Room, she surely responds to that litany of delicate nudity (painted by men!) which made up so much of 19th and 20th century art. Her subject has the pose of Titian’s Venus or Manet’s Olympia — but totally and quite powerfully subverts everything else about those paintings and the genre they represent:

But we shouldn’t be surprised, because Valadon was something like force of nature. She was born to a poor washerwoman and never knew her father, and had no choice but to work from a young age. Her dream was to join the circus, and the dream was achieved; falling from a trapeze and injuring her back, aged fifteen, ended that dream. So she turned to art, working as a model for the leading avant-garde artists of the day, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec among them, all of whom were living in her native Montmartre. And, after modelling for them, having taught herself to draw and learned from them, Valadon joined them. She even took on the biblical name Suzanne herself (she was born Marie-Clémentine) and subverted that very name and its associated story as only she could. This was a person who wrote her own story in life — and this monumental personality is also revealed, I think, in Valadon’s art.

IV - Architecture

St Anne’s Cathedral

Vilnius, Lithuania

This quite remarkable building is even more remarkable when we realise that it is over five hundred years old. Had it been constructed in the late 19th or early 20th centuries (as it looks) then we would be impressed enough; that five centuries have not dimmed its splendour is a testament to the genius of its builders!

But St Anne’s is not wholly unique. It is, rather, a supreme example of an architectural style known as Brick Gothic. This was, as the name suggests, a subgenre of the Gothic Architecture which dominated Western, Southern, and Northern Europe from the 12th to the 16th centuries. And, as the name also suggests, its defining characteristic is that its prime material was bricks (rather than, as elsewhere, stone). St Mary’s Cathedral in Gdańsk, Poland, is a good example of Brick Gothic at its most monumental:

Brick Gothic was most common in the Netherlands, Denmark, and around the Baltic — all low-lying, coastal places where stone was not easily procured and bricks were therefore a more expedient choice. Just such a place was Lithuania, and its capital Vilnius, home to one of the world’s best preserved Medieval cityscapes. Among its many jewels is this church, St. Anne’s, built from about 1495-1500 under Grand Duke of Lithuania and later King of Poland Alexander I Jagiellon. It’s only small — a single nave without aisles — but makes up with imagination and exuberance and charm what it lacks in scale.

The campanile (free-standing bell tower) to its right was built in the 19th century, though in a congruous Neo-Brick Gothic style; the building behind is the much-larger Church of St Francis and St Bernard, another lovely work of Brick Gothic, though with the additions Renaissance and Baroque meddling in the 16th and 17th centuries.

What defines the Brick Gothic as a style? Material is not its sole idiosyncrasy. Along with a variety of regional traditions (think of the famed stepped gables of the Netherlands), the very nature of bricks lent themselves to further architectural motifs that set it apart from Western or Southern Gothic. There is, for example, a distinctive lack of sculpture: no gargoyles, saints, or angels clustered around doorways or peering down from towers. As a result, Brick Gothic churches relied for their decoration on the interplay of pattern and colour instead:

There is something of an aesthetic dissonance about the Brick Gothic. We see a material — bricks — usually associated with solidity, and even a kind of domesticity, used to create forms — the spiralling tracery and cascading pinnacles of the Gothic — that are much grander and more dramatic. But this disonnance is not a bad thing; it is what makes Brick Gothic such a striking style.

It’s also a reminder of what’s possible even with the humblest of building materials, and one we still use all the time. London (for example) is filled these days, and increasingly so, with this sort of thing. They’re fine… but incredibly generic, wholly without character, and just a bit boring.

Might the old Hanseatic cities of the North Sea coast, the mercantile hubs of the Low Countries, and the great towns of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth offer some inspiration for our modern brick-based architecture? I say they ought.

V - Rhetoric

Epanadiplosis

Alida Valli says in The Third Man:

A person doesn’t change the more you know about them.

True — they don’t. But we who know more do change.

Such is the power of epanadiplosis. It’s a quite simple rhetorical device: when you begin and end a sentence with the same word or phrase. No doubt this is something you’ve noticed before; now you know what to call it.

But epanadiplosis can be extended beyond a single sentence, as when a whole paragraph or stanza of a poem begins and ends with the same word or phrase. We can go even further. When a book begins and ends with the same words, or even the same idea or image, that is also epanadiplosis. And this needn’t just be written: if a film begins and ends with the same scene or image, that’s also epanadiplosis. The same for music and a particular motif that opens and closes a piece.

Fight Club, Gone Girl, The Prestige, Oppenheimer, and Gladiator are five films that use epanadiplosis in this way. The beauty of this device is twofold. First, it creates a wonderful sense of completeness, of having come full circle. Second, and in concordance with the first point, the beauty of epanadiplosis is that when we return to those starting words, ideas, or images, our understanding of them —how they make us feel — has changed, even though they remain the same. The raindrops of Oppenheimer or the wheatfields of Gladiator do not change between the opening and closing of these films; it is we who have changed, and what we have seen that has changed us.

And (returning to its narrower meaning) all of this this is true even when we use epanadiplosis in a single sentence. Consider this legendary exclamation, and how precisely the same word has two totally different meanings each time we hear it:

The King is dead; long live the King!

(Anadiplosis is the inverse: when a new sentence or clause begins with the word that ended the previous sentence or clause. Think of Yoda saying: “Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.”)

VI - Writing

Grammarless!

A few weeks ago, for the first time in about five years, I needed to do some work but did not have my own familiar laptop to hand. So I had to use somebody else’s. And, it turned out, they had a certain app (or extension?!) called Grammarly installed.

For those who don’t already know, this is a bit of software that finds errors or suggests improvements in real-time as you type, on any given website. Already, writing this paragraph, every single sentence has been defaced with at least one line, variously of pink or yellow or green. These signify “errors”, and each time I cease typing for more than a few seconds a little red flag unfurls alongside the cursor. It is emblazoned, in white sans serif, with a slogan offering to “fix” those errors. Worse still, it keeps telling me that everything I’ve written could be improved, suggesting synonyms or concisions or alternative punctuation.

In the face of this pest, I ask: “to what end?”

I suppose it is a tool. The question, then, is whether this tool makes us better writers and better thinkers. What do you believe? I have said it before and will go on saying that Shakespeare spelled his own name six different ways, and that both he and pretty much every writer worth their salt was not worth that salt because of the extent to which they complied with the orthographical standards of the day! No bit of writing was ever improved because its spelling was corrected or punctuation altered. The highest virtue of correct spelling is merely professionalism; a worthy end, certainly, but professionalism is far from the highest virtue of writing in general, or of human imagination and endeavour.

Every technology does something for us we would otherwise have to do ourselves. In which case, every time we think about using a particular technology, we must ask whether we would be better off doing that thing ourselves or letting the technology do it for us. Better to delegate our grammar and syntax and orthography to Grammarly… or better to actually learn and master those things, and become better writers thereby? No doubt it “saves time” (like most technologies) but that in itself isn’t a good reason to do anything — watching our favourite films on 2x speed would also save time! The time saved by relying on Grammarly isn’t worth the advantage gained by investing time in learning to do what it proposes to do for us. Of this I am sure.

Besides, I find there’s something creepy about having one’s words meddled with (by an invisible third party) as one is writing them. Writing is thinking, and having your thoughts edited live by an Artificial Intelligence doesn’t seem healthy to me. At the very least, I am convinced, it will neither make us better writers nor thinkers.

VII - The Seventh Plinth

From Four to Four Hundred (or so…)

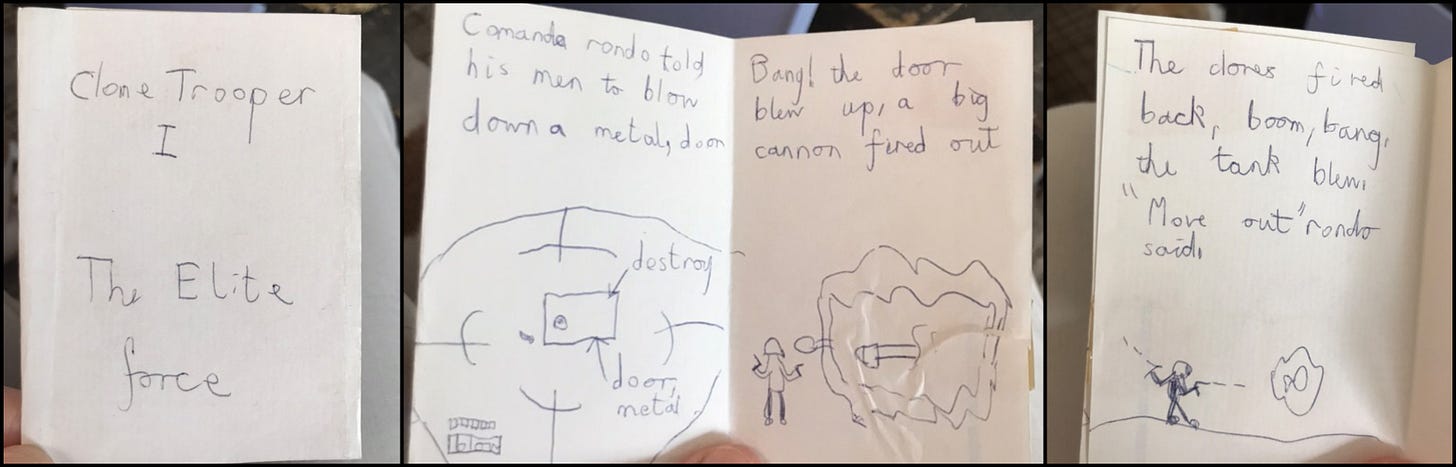

It was twenty three years ago, shortly after the release of Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones (it seems) that I wrote my first book. It was four pages long, including the cover, and went like this:

Two and three tenths of a decade later, as I mentioned at the outset of this newsletter, copies of my first “real” book have arrived, which is a little longer. It’s probably too long (like most books) and on the whole I agree with Thomas Dekker, anyway, that:

We should come to the presse as we come to the fielde (seldom).

Still, I share this little anecdote because, somehow, I think it means something. I know that many of my readers are already writers, in the sense that they write, but have not yet arrived at the place they want to reach, wherever precisely that this. Well, if even just one of you, reading these words, likes to write — more than likes, feels a compulsion to write — but on this particular day is struggling to do so, even considering giving up, I hope this comparison — of a little book written twenty three years ago, marking the start of a dream, and the final realisation of that dream after long periods when it seemed unreachably distant — encourages you to not give up. In future I may offer more concrete advice, but for now this is the vitallest and enduringest point: keep writing.

Question of the Week

Last time I set you the challenge of writing something inspired by or based on a painting. Here were some of your responses:

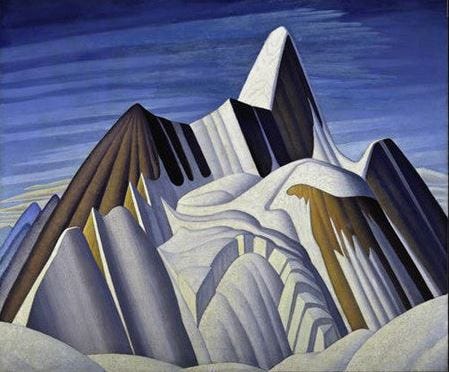

Rik J

Early morn first breath

Edges carve a fresh laid blanket

Silence sings in speedAlthough its been many years since, when I was younger some of my most precious memories are being the lucky one to be the first to ski a fresh powder slope. Its noisy and silent simultaneously. Slow and calm while also feeling a sense of thrilling speed.

The feel of gliding on the new snow, hearing that unique hiss of skis as you slowly weave your way down, compares to no other experience I've had.

Mount Robson by Lawren Harris of the Group of Seven reminds me of that feeling whenever I see it, and inspired the terrible haiku written above.

Michael M

In writing about the US civil war during the first several decades after its ending, that conflict often was described, in Southern writings, as "the late unpleasantness".

This was a euphemism meant to gloss over a variety of details that some portions of the defeated South did not want emphasized.

(Euphemisms do this - gloss over detals. A few other examples include:

Baden Powel's emphasis of a "regular daily rear" (for daily bowel movements) in the 1908 edition of his Scouting for Boys; Japanese describing their female sex slaves as "comfort women" during WW2; Early Northern Europeans who were so terrified of bears that they referred to the bears as "the brown ones" hoping that not saying the name would not beckon the bears.)

This painting shows two West Point grads (Grant, class of 1843, and Lee, class of 1829) shaking hands in a civil, friendly, genteel manner to end the "unpleasantness".

Although "a picture is worth a thousand words," this painting does not show, among other things: Southern leaders tried to dissolve the Union so that Southerners could continue and expand slavery; Southern leaders, during the war, called the conflict a civil war; Lee, Davis, and other Southern leaders who previously had taken an oath to defend the Constitution were traitors; For peace to occur, Southern leaders had to stop their rebellion; and Southern leaders would not end their rebellion voluntarily; they had to be forced to end their rebellion - which General Grant did.

Because Southern leaders chose to rebel, the conflict to save the Union resulted in some 1.5 million US casualties, about half of which were deaths, and the destruction of the South's slave-based economy. This is but one example showing the necessity of examining multiple sources when seeking to understand historical events.

"Let Us Have Peace", a well known painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

Jacob C

As for the writing exercise you have prescribed, even before I have penned down a single word I wish to attend you to the beautiful song 'Parel' by Spinvis. It is about Vermeers famous 'Girl with a Pearl Earring'. Please do give it a listen. The lyrics (in English for your understanding) are as follows;

I'll call you 'little bird'

I'll call you 'riddle said"

You saw the spring on the shores

The horses in the countryside

I'll call you 'fiction'

I'll call you 'falling rain'

After everything was said

I'll call you here and now and real and unattainableThe entire world in a frame

The tourist come and go

When they've left you just stay here

A thousand years away

A child sees the same light

On your pearlescent face

I've known you for a bit

In a neverending momentI'll call you homesick

I'll call you swallow

On souvenirs and umbrellas

In blue and white and yellow

Silence in shadow

I'll call you mirror

I'll call you heartbeat

I see you in a shopping street

As you turn the corner

In every little smileThe entire world in a frame

The tourist come and go

When they've left you just stay here

A thousand years away

A child sees the same light

On your pearlescent face

I've known you for a bit

In a neverending momentI'll call you 'little bird'

I'll call you 'fiction'

I'll call you 'riddle said'

I'll call you 'pearlescent'

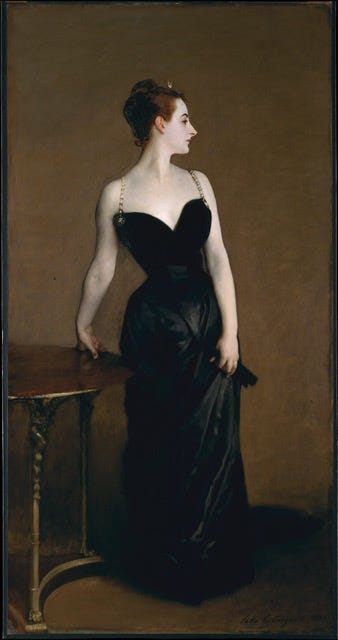

Samreen N

What I’m not:

Not the siren, no Madonna,

I’m not the label you give me.

Not fragile in mind or spirit,

I weathered more storms than you.

I’m not the damsel you imagine me.What I am:

I’m the sunlight reflected from ice.

I’m the raven in the night.

You see glimpses of me,

You try to paint my picture.

I’m the purgatory hidden in plain sight.

And for this week’s question, given the special occasion of this hundredth edition, I suppose it’s time that I switched things up:

Rather than me asking you a question… why don’t you ask me a question? It can be about anything at all!

Email me your questions and I’ll answer them in the next Areopagus.

And that’s all

Where next? Onwards! “If anything remains to be done, nothing has been done.” So said Julius Caesar (or Octavian?) as quoted by Michel de Montaigne, or at least so far as I remember it, looking back on a dimly-lit night some two years ago in “the bunker” (as we called it) with my dear friend Harry. Caesar’s aphorism sounds excessive; one must celebrate the small victories! But much work doth remain — and remains for me to get to it. This Areopagus (ever ongoing!), the book (now written), and two more as-yet-unannounced projects in the works. One at a time. The dream of a beautiful education — for one and all — is still being dreamed. We’re all part of it; we’ve done well; we have far to go.

Today concludes with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, with a few lines from the sixth of her Sonnets from the Portuguese:

The widest land

Doom takes to part us, leaves thy heart in mine

With pulses that beat double. What I do

And what I dream include thee, as the wine

Must taste of its own grapes. And when I sue

God for myself, He hears that name of thine,

And sees within my eyes the tears of two.

Yours,

The Cultural Tutor